SANTA MARIA DEL NARANCO

Previous notes

- Declarado Monumento Nacional en 1885 y como Patrimonio Mundial de la Humanidad por la UNESCO, inscrito con otros monumentos prerrománicos asturianos con el nombre de “Iglesias del Reino de Asturias”, en 1985.

- Sufrió diversas modificaciones en el periodo gótico y principalmente durante el barroco, fase en la que se derribó el muro sur y se tapiaron los vanos centrales del mirador oeste para construir una rectoral y una sacristía.

- Fue restaurada entre 1929 y 1934 por L. Menéndez Pidal, eliminando todos esos añadidos y recuperando su estructura y aspectos originales.

Historic environment

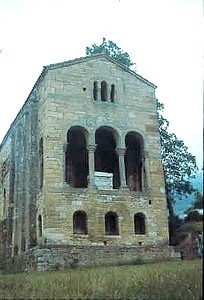

This palace built by Ramiro the First together with San Miguel de Lillo and possibly Santa Cristina de Lena during the 8 years of his reign (842-850) is, from our point of view, the most important monument preserved of High Medieval European Art. Both fot its intrinsic value as well as for being a compendium of the best building techniques that come from former periods and, above all, for the roads it opened later to all the art in general.

Description

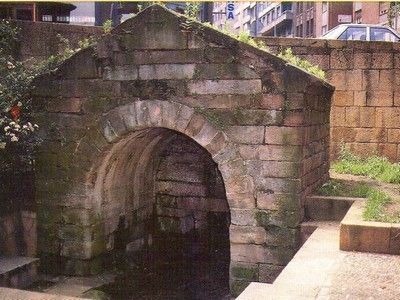

It is a recreational palace of 20 meters long by around six meters wide and eleven meters high. Built with small very well squared ashlars in horizontal courses with two overimposed naves, both covered with grainsand vaults on perpiaño arches. Located in a place where, besides the San Miguel de Lillo church, there were also some other service buildings that do not any longer exist. This type of structure was already very well known in Spanish Pre-Romanesque Art, with precedents of such importance as the Mausoleo de La Alberca, Santa Eulalia de Bóveda, the crypt of San Antolín in Palencia and, already in the Asturian period, the Holy Chamber of the Cathedral of Oviedo. All of them were double vaulted buildings, except the first one, of which only a few rests remain. The other ones have preserved their lower nave almost intact, but this one is the only case where the upper nave has also been completely preserved, not only because Asturias did not suffer the invasions nor was in the avant garde of any war as the former three, but also due to its exquisite quality of design and construction, very stunning for a ninth century building.

vaults on perpiaño arches. Located in a place where, besides the San Miguel de Lillo church, there were also some other service buildings that do not any longer exist. This type of structure was already very well known in Spanish Pre-Romanesque Art, with precedents of such importance as the Mausoleo de La Alberca, Santa Eulalia de Bóveda, the crypt of San Antolín in Palencia and, already in the Asturian period, the Holy Chamber of the Cathedral of Oviedo. All of them were double vaulted buildings, except the first one, of which only a few rests remain. The other ones have preserved their lower nave almost intact, but this one is the only case where the upper nave has also been completely preserved, not only because Asturias did not suffer the invasions nor was in the avant garde of any war as the former three, but also due to its exquisite quality of design and construction, very stunning for a ninth century building.

It is very difficult to describe in these few lines such a perfect work for its times. On the outside we find ourselves with a rectangular building with a pitched roof, upon a stone plinth that visually consists of three horizontal zones, separated by stripes in stone in a different colour, of which the first one corresponds to the lower nave and the other one to the upper one. The ensemble thus created produces an overwhelming sensation of verticality. At the centre of the northern and southern sides, that correspond with the largest sides of the rectangle, there are two doors that end in round arches, that give way to each of the plans; whereas in the northern side there is a double staircase that gives access to the central portico of the upper floor, almost with the same height than the lateral walls and reinforced by buttresses. In the southern side, the door opened to a viewpoint, now disappeared, protected by a portico, possibly of the same type as the former ones but without any staircases. As we have mentioned, each one of these porticos protects an entrance door to the lower floor, that is placed immediately under the upper one. The lateral walls that finish in four windows, two of which correspond to an existing row of balconies at every end of the upper floor and the two others to a lateral chamber placed under each row of balconies on the lower floor; have eight buttresses, four at each side of the porticos with strias’ decoration as we will also see in the interior.

find ourselves with a rectangular building with a pitched roof, upon a stone plinth that visually consists of three horizontal zones, separated by stripes in stone in a different colour, of which the first one corresponds to the lower nave and the other one to the upper one. The ensemble thus created produces an overwhelming sensation of verticality. At the centre of the northern and southern sides, that correspond with the largest sides of the rectangle, there are two doors that end in round arches, that give way to each of the plans; whereas in the northern side there is a double staircase that gives access to the central portico of the upper floor, almost with the same height than the lateral walls and reinforced by buttresses. In the southern side, the door opened to a viewpoint, now disappeared, protected by a portico, possibly of the same type as the former ones but without any staircases. As we have mentioned, each one of these porticos protects an entrance door to the lower floor, that is placed immediately under the upper one. The lateral walls that finish in four windows, two of which correspond to an existing row of balconies at every end of the upper floor and the two others to a lateral chamber placed under each row of balconies on the lower floor; have eight buttresses, four at each side of the porticos with strias’ decoration as we will also see in the interior.

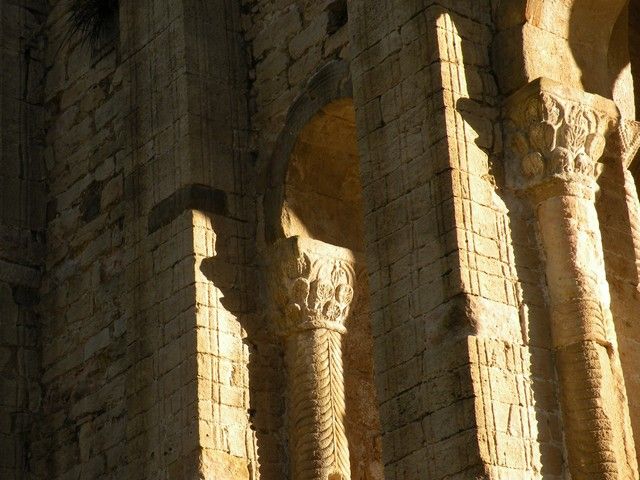

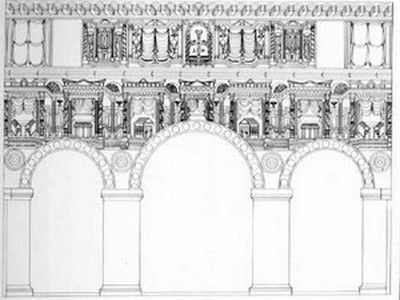

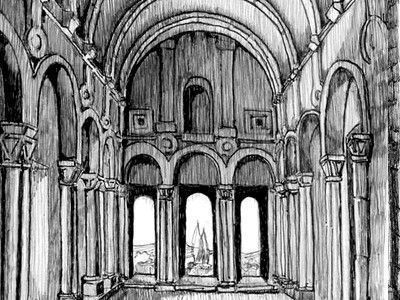

Special mention des erve the two façades at the ends. In both of them, totally symmetrical except in their lower part, become more important in the three horizontal zones, each one of them with a different structure, but forming part of a common design of golden section and great beauty, The lower zone, which on its east side counts with three windows that end in round arches has just one door in the nave’s entrance. Upon it and in both of them, a great balcony opens in the front with three casted round arches, being the central one larger than the lateral ones that lean on the sides upon columns with roped decoration and capitals of the degenerated Corynthian type; the laterals attached to the walls and two arches at each side separated by pillars that correspond to a buttress at the exterior, with columns and capitals attached, of the same type as the former ones. In the columns we can still see the supporting slots of the stone parapets that closed the whole of the row of balconies. In the last zone there is a window, also a three-arched one; each one of them with two small columns and two capitals, being the central one larger, creating a sort of a copy of the lower row of balconies but much smaller. This window is framed within two vertical decoration stripes that start from medallions with representations of animals, located between the arches of the lower zone. It is interesting to notice that this window as well as the ensemble of the row of balconies seem to have been made as an imitation of the threee-arched window in the upper part of San Julián de los Prados’ and San Pedro de Nora’s chevets.

erve the two façades at the ends. In both of them, totally symmetrical except in their lower part, become more important in the three horizontal zones, each one of them with a different structure, but forming part of a common design of golden section and great beauty, The lower zone, which on its east side counts with three windows that end in round arches has just one door in the nave’s entrance. Upon it and in both of them, a great balcony opens in the front with three casted round arches, being the central one larger than the lateral ones that lean on the sides upon columns with roped decoration and capitals of the degenerated Corynthian type; the laterals attached to the walls and two arches at each side separated by pillars that correspond to a buttress at the exterior, with columns and capitals attached, of the same type as the former ones. In the columns we can still see the supporting slots of the stone parapets that closed the whole of the row of balconies. In the last zone there is a window, also a three-arched one; each one of them with two small columns and two capitals, being the central one larger, creating a sort of a copy of the lower row of balconies but much smaller. This window is framed within two vertical decoration stripes that start from medallions with representations of animals, located between the arches of the lower zone. It is interesting to notice that this window as well as the ensemble of the row of balconies seem to have been made as an imitation of the threee-arched window in the upper part of San Julián de los Prados’ and San Pedro de Nora’s chevets.

At the interior, the lower part consists of a main nave and two compartments at the extremes that correspond to the row of balconies of the upper plan. The main nave is vaulted upon perpiaño arches that lean on a base forming a structure very similar to San Antolín de Palencia and the Holy Chamber of Oviedo, and the aisle  has a wooden roof. Whilst the western one has a door that

has a wooden roof. Whilst the western one has a door that

opens to the outside and is not communicated with the main nave (probably it had to do with the guard corps), the east side one that was a bath house, from which rests of a pool have appeared that had a water supply from outside, had the only access from the main nave and the three windows to the outside which we have mentioned already.

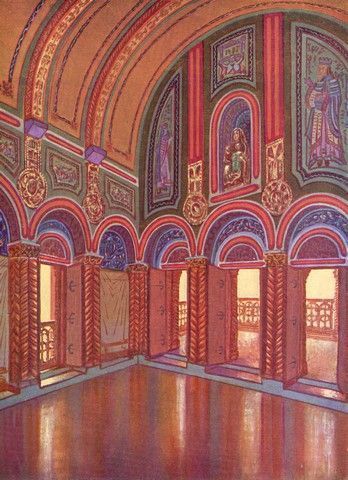

It is in the upper plan where we can properly value the merits of the unknown architect and of the whole of the team of builders that created it. Completely symmetrical with regard to both axes, it is also divided in three bodies. The main one is a great vaulted nave upon six perpiaño arches that lean on four column bundles under a sole capital that corresponds to the exterior buttresses and that form the base of a blank series of arches upon the lateral walls, supporting besides perpiaño arches, through arches formed by a corbel and a decorated pilaster and a medallion like those described for the row of balconies; all of that placed upon the the capital’s vertical. In the series of arches, two windows open at each side and a rectangular door, and upon the central arch, the widest one, there is a seventh perpiaño arch. We have to point out that the series of arches continue to reduce their size as they get farther from the centre, which produces a depth effect which is undoubtedly what the architect was looking for. The also symmetrical extremes of this naves communicate with the lateral row of balconies through three areches, somewhat wider than the main one, thus generating the described structure: arches supported upon four-column bundles, a capital, a medallion and one in the shape of the decorated pilaster; in this case only with decorative motifs. Through them, that also have rectangular doors, the  view of the Asturian landscape filtered through the beauty of these arches and the decoration of the row of balconies is as exquisite a the building itself. The interior of the row of balconies keeps the same architectural and decorative rhythm than the main nave, vaults upon perpiaño arches with column bundles, capital, decorated medallion and pilaster, as well as blank series of arches in the separation wall with the main nave and crystal clear at the sides. In both cases the interior arches are larger than the exterior ones and than those of the main nave, leaned in this case upon the wall and on pilasters at the sides. Later to its building, maybe to the partial collapse of San Miguel de Lillo, this palace was converted into a church, for which an altar was added at the east viewpoint, with the dedication of another church -supposedly the one we now call San Miguel- by Ramiro the First to the Virgin Mary, that is still preserved, though the original one has been replaced by a copy.

view of the Asturian landscape filtered through the beauty of these arches and the decoration of the row of balconies is as exquisite a the building itself. The interior of the row of balconies keeps the same architectural and decorative rhythm than the main nave, vaults upon perpiaño arches with column bundles, capital, decorated medallion and pilaster, as well as blank series of arches in the separation wall with the main nave and crystal clear at the sides. In both cases the interior arches are larger than the exterior ones and than those of the main nave, leaned in this case upon the wall and on pilasters at the sides. Later to its building, maybe to the partial collapse of San Miguel de Lillo, this palace was converted into a church, for which an altar was added at the east viewpoint, with the dedication of another church -supposedly the one we now call San Miguel- by Ramiro the First to the Virgin Mary, that is still preserved, though the original one has been replaced by a copy.

A pictorical decoration must have existed but nothing is left of it. Regarding the sculpted decoration that was entirely developed for this building as a structural element in most of cases and within a complete previously defined programme as a part of the architectural design, is as interesting as everything we have defined up till now. It seems unquestionable that it was developed by a sole team of quarrymen with a diffferent technique to the Visigothic bevel, rounding the edges to get a much softer and real effect, but with very different influential motifs among which several groups could be defined:

- The capitals: two types basically, the degenerated Corynthian of the row of balconies of classical

precedent, and the truncated pyramidal interiors of Byzanine type, but with very varied decoration, with conflicting animals of clear oriental influence till silhouettes of monks which have been related to the Irish art.

precedent, and the truncated pyramidal interiors of Byzanine type, but with very varied decoration, with conflicting animals of clear oriental influence till silhouettes of monks which have been related to the Irish art.

- The medallions: which external ornamentation with interwined chords or circles is of clear Hispanic tradition, but the interior, generally decorated with conflicting animals is oriental also. In these medallions, which clear precedents are the concentric circles painted between the arches of San Julián de los Prados, some Viking influence has been tried to establish.

- span style=”text-decoration: underline;”>The pilasters: upon the medallions with monastic and knight silhouettes, also related to the Irish art.

- The columns: with roped decoration, also of Hispanic-Visigothic origin.

In summary, we find ourselves in front a perfectly documented monument, of which we know the exact building date, who ordered the building, its objective as well as the artistic surroundings of its time and the geographical situation; but in spite of all of that, it is impossible to explain to ourselves how an architect at his atelier, in such a far away place of the world could put together so much knowledge and styles without any shadow of

could put together so much knowledge and styles without any shadow of

mistake in a so clearly planned work in all of its components and details. In fact, from the architectural point of view, we find ourselves before a palace with similarities with the late Roman palaces and with the German “Halls”, but with two overimposed naves of Roman tradition and many Hispanic precedents in the funerary and religious architecture, with grainsand vaults upon perpiaño arches, what has been associated to Roman and Oriental influences, and that uses as a basic decorative structure, three-arch ensembles, which precedent seems to be San Vital de Rávena through Visigothic monuments like San Fructuoso de Montelios. But from the point of view of the sculptured decoration, the analysis is, at least, as complex: the technique, without any precedents in previous monuments and common in all of its elements, which makes us think it was developed by a sole atelier, is based in the one utilized in the Visigothic period, though with important differences, and for the motifs, precedentts can be found from practically the whole world known at that time, that could have been copied from drawings on textiles and documents. But, in times where communcations were so difficult, riskful and slow and there was no possibility of transcribing architectural information through reliable drawings, it becomes impossible to understand how up to the last detail could have been previously and thoroughly planned, and build with total perfection, developing a sculptoric ensemble so varied and at the same time so homogeneous despite containing that diversity of influences in such a complex and original work which has no precedents at all.

Conclusions

Which genial architect, and with which atelier could have turned in less than a decade the characteristics of the Asturian art of the operiod of Alphonse the Second, based in buildings of horizontal structure, thick walls, pillars, wooden covers and almost a lack of sculptoric decoration, in verticality, lightness, utilization of columns grainsand vaults upon perpiaño arches and very complex sculptoric programmes, and all of that previously designed up to the minimum detail, that we observe in the building of Naranco, composing a totally mature set of technique and art without any previous period of gestation of the new style?

All the efforts that have been made to relate some given components with monuments located in Italy, Greece, Ireland and even Syria and Persia, only serve to reject the idea that an Asturian architect could have visited  those countries and learn each one of the techniques and styles to create on his return, his own atelier and apply these techniques later in Santa María del Naranco with such security. We have still two other possibilities left: one would be the arrival to Oviedo of a team of foreign builders with a great experience that, as it happened later during the Roman and Gothic periods, could have accepted the assignment. This would be the most reasonable possibility, especially because it is the only way to explain the presence of a complete homogeneous team of builders, but the fact that there is no documentation left and that there are neither in Spain nor in the rest of Europe buildings that could be attributed to the same team, make this idea quite improbable. Another thing would be to think that the most part of these influences had been already present in monuments of previous centuries that were still standing in the north of Spain, so that an exceptional architect both technically and artistically and with an extraordinary capacity to form and lead a team, could have been able to desing and lead in just eight years three works of the magnitude of Santa María del Naranco, San Miguel de Lillo and Santa Cristina de Lena, learning from the surroundings and from any information he mght have gotten from abroad. This possibility, though with all the logical reservations, seems to us the most probable one as in the reconquered area at that time some monuments that could have inspired him are still preserved, like the Holy Chamber, San Pedro de la Nave, San Fructuoso de Montelios or Santa Eulalia de Bóveda and we know that in times of Ramiro the First many other buildings from the Roman and/or Visigothic periods, like the Villa de Veranes besides all of the previous Asturian architecture that also obviously exerted its influence, and could have been also a reference that unfortunately has not persisted.

those countries and learn each one of the techniques and styles to create on his return, his own atelier and apply these techniques later in Santa María del Naranco with such security. We have still two other possibilities left: one would be the arrival to Oviedo of a team of foreign builders with a great experience that, as it happened later during the Roman and Gothic periods, could have accepted the assignment. This would be the most reasonable possibility, especially because it is the only way to explain the presence of a complete homogeneous team of builders, but the fact that there is no documentation left and that there are neither in Spain nor in the rest of Europe buildings that could be attributed to the same team, make this idea quite improbable. Another thing would be to think that the most part of these influences had been already present in monuments of previous centuries that were still standing in the north of Spain, so that an exceptional architect both technically and artistically and with an extraordinary capacity to form and lead a team, could have been able to desing and lead in just eight years three works of the magnitude of Santa María del Naranco, San Miguel de Lillo and Santa Cristina de Lena, learning from the surroundings and from any information he mght have gotten from abroad. This possibility, though with all the logical reservations, seems to us the most probable one as in the reconquered area at that time some monuments that could have inspired him are still preserved, like the Holy Chamber, San Pedro de la Nave, San Fructuoso de Montelios or Santa Eulalia de Bóveda and we know that in times of Ramiro the First many other buildings from the Roman and/or Visigothic periods, like the Villa de Veranes besides all of the previous Asturian architecture that also obviously exerted its influence, and could have been also a reference that unfortunately has not persisted.

In summary, we think that a visit to Santa María del Naranco is indispensable to know the high levels of quality reached the Spanish Pre-Romanesque Art, one of the first and most interesting precedents of the European Romanesque Art.

Other interesting information

Access: Go up from Oviedo’s downtown to the Naranco Hill through Padre Vinjoy, Hermanos Menéndez Pidal,Teniente Coronel Teijeiro and Ramiro I from the Plaza de la Paz ; then follow the signals. GPS Coordinates: 43º 22′ 44,71″N 5º 51′ 57,57″W.

Information telephone: Parish priest: 985 212 660 (D. José Luis Pascual Arias). Visits: 638 260 163

Visiting hours: The last visit starts always half an hour before closing.

– Winter (October through April): Tuesdays to Saturdays: 10 to 13 and 15 to 17. Sundays and Mondays: 10:00 to 13:00.

– Summer (May through September): Tuesdays to Saturdays: From 9:30 to 13:30 and 15:30 to 19:30. Sundays and Mondays: 9:30 to 13:30.

Bibliography

Arte Pre-románico Asturiano: Antonio Bonet Correa

SUMMA ARTIS: Tomo VIII

L’Art Preroman Hispanique: ZODIAQUE

Ars Hispanie: Tomo II

Arte Asturiano: José Manuel Pita Andrade

Guía del Arte Prerrománico Asturiano: Lorenzo Arias Páramo

Portals

Santa Maria del Naranco y San Miguel de Lillo (Página Oficial)

El Arte de la Monarquía Asturiana – Santa María del Naranco

La intervención en la arquitectura prerrománica asturiana: Jorge Hevia Blanco, Gema Elvira Adán Álvarez

Santa María de Naranco