SAN MIGUEL DE LILLO

Previous notes

- Declarado Monumento Nacional en 1885 y como Patrimonio Mundial de la Humanidad por la UNESCO, inscrito con otros monumentos prerrománicos asturianos con el nombre de “Iglesias del Reino de Asturias”, en 1985.

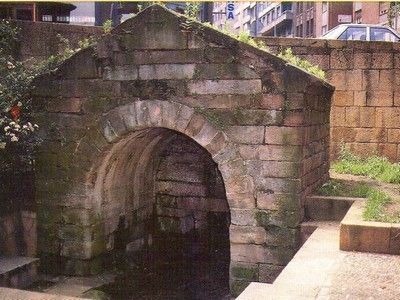

- En la Edad Media, hacia el siglo XI, un desplazamiento de tierras destruyó los dos tercios más orientales de la iglesia, por lo que se cerró a partir del primer tramo de las naves con un muro y un ábside.

- En 1850, bajo la dirección de Andrés Coello se efectuó una primera intervención efectuando obras de conservación y reparación y eliminando todos los elementos añadidos a lo largo de diez siglos, para dejarla en su aspecto actual.

- A lo largo del siglo XX ha sufrido diversas intervenciones arqueológicas y de restauración, la última de ellas, efectuada por el Instituto Arqueológico Alemán en 1989/90 ha permitido reconstruir con suficiente fiabilidad su planta original.

Historic environment

According to all the chronicles of the time, Ramiro the First gave the order to build this church, located at 300 steps of the palace that today we call Santa María, as a part of the resting residence that he created at the Naranco Hill’s southern side. All its characteristics indicate that he engaged the same architect and that he used the same atelier. Unfortunately only a third part of the original building has reached to these days, since the whole chevet and part of the naves collapsed, possibly in the twelfth century, apparently due to a land displacement provoked by a near stream. After the excavations that took place at the beginnings of the last century, to day we know, not only the part that still survives, but also all its original plan.

Description

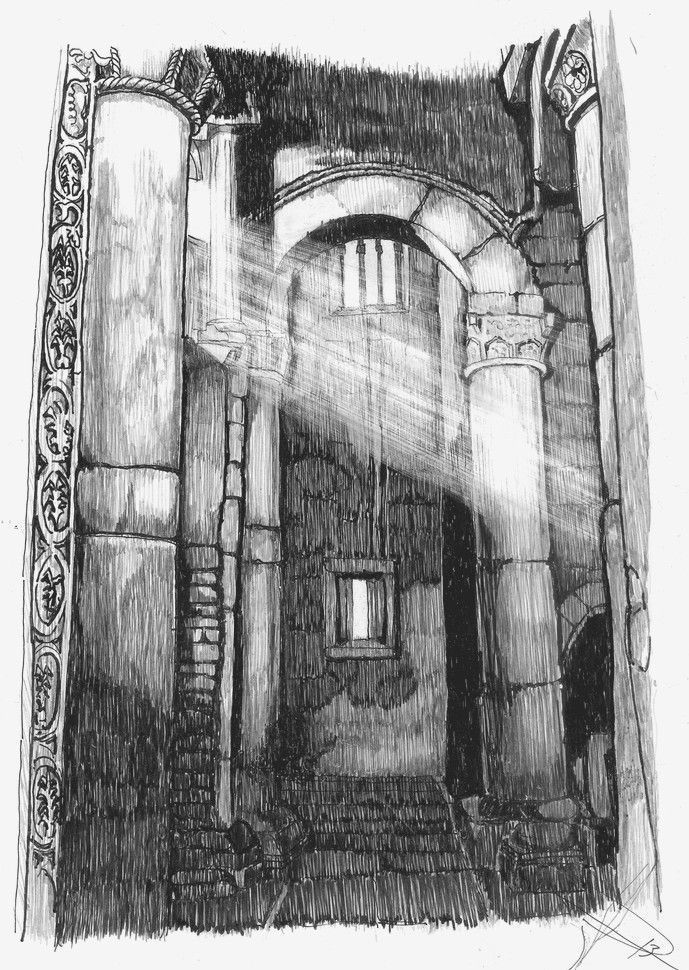

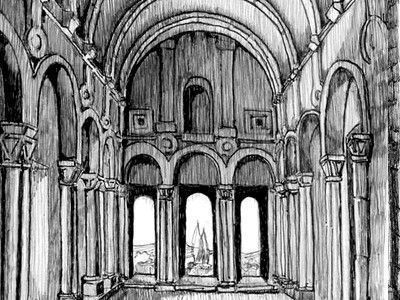

If, as we have mentioned, all the Ramirense art seems to us an almost total breaking with the previous Asturian art, San Miguel de Lillo is the most evident example. It was a basilical plan church  of 15.85m long by 10.05m wide and up to 11m high in the central nave; with three naves, three square apses of equal depth but the central one being wider than the lateral ones; two compartments, one at each side of the crossing, and with an inner portico that supports a tribune that has access through two staircases, each one located in a lateral compartment of the portico. So far, it does not look that different, but let us analyse its structure.

of 15.85m long by 10.05m wide and up to 11m high in the central nave; with three naves, three square apses of equal depth but the central one being wider than the lateral ones; two compartments, one at each side of the crossing, and with an inner portico that supports a tribune that has access through two staircases, each one located in a lateral compartment of the portico. So far, it does not look that different, but let us analyse its structure.

- Different to the previous Asturian buildings, San Miguel was completely vaulted and the separation with the naves was achieved through arches upon columns instead of pillars. The main nave, of 11m high by just 3.35m wide had a sandgrain vault upon perpiaño arches reinforced with exterior buttresses, similar to Santa María del Naranco, which produces the sensation of verticality that seems to anticipate the Romanesque art, completely opposite to the horizontal

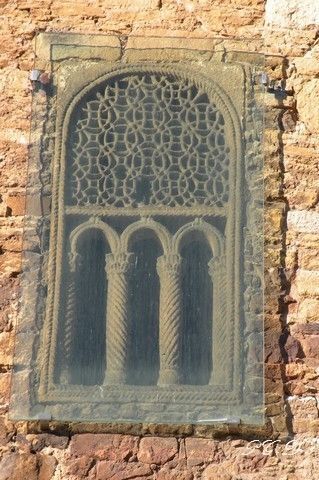

trend that dominates in churches of the previous period, like for instance, in San Julián de los Prados the main nave is 7m wide by 10m high and has a flat wooden cover. In the aisles, even a more original system was used: instead of having just one vault as a main nave, these have in each stretch an independent vault, with the peculiarity that they are perpendicular between them and of a different height; higher the perpendicular ones to the main one, where large windows opened with lattice cut out in stone of magnificent decoration. We can find only one close precedent to this collection of vaults independent on each nave’s stretch in Santa Lucía del Trampal’s chevet.

trend that dominates in churches of the previous period, like for instance, in San Julián de los Prados the main nave is 7m wide by 10m high and has a flat wooden cover. In the aisles, even a more original system was used: instead of having just one vault as a main nave, these have in each stretch an independent vault, with the peculiarity that they are perpendicular between them and of a different height; higher the perpendicular ones to the main one, where large windows opened with lattice cut out in stone of magnificent decoration. We can find only one close precedent to this collection of vaults independent on each nave’s stretch in Santa Lucía del Trampal’s chevet. - Whilst the triple chevet was already usual in Asturian art, its general structure is closer to some cruciform Visigothic churches, with three vaulted naves and without any separation of areas between the naves and the chevet, like San Pedro de la Nave or Quintanilla de las Viñas, and with a tribune upon an inner portico that we find already in the mentioned Quintanilla and San Giao de Nazaré.

- Different to the previous period, there is a very rich sculptured decoration developed for this building and a great part of it upon structural elements, like in Santa María del Naranco, which shows that San Miguel was also built following a previous perfectly defined plan.

- It is important to point out that the quality that Ramiro the Fist’s architect had was so exceptional, that in the following period all the recorded characteristics were lost except in San Salvador de Valdediós where, though going back to the utilization of pillars, a similar ratio was kept between height and width in the main nave, and consequently, the sensation of verticality, though in a much a heavier ensemble.

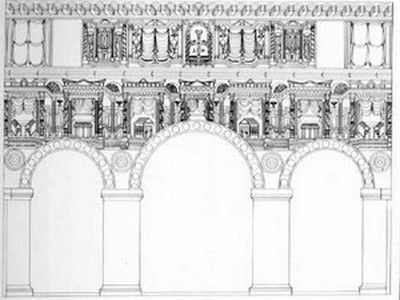

Its volume design was very complex in the outside due to the buttresses and to the different heights of the portico,  the main nave and the two kinds of aisles. Its structure must have been very original for those times, since the two highest aisles, which only the western one has been preserved, would produce the false feeling that the church had two transverse naves as if it had two crossing naves. Its main façade is the most interesting one in all Spanish Pre-Romanesque art. Its composition consists of four different plans: in the portico’s lower part and in the wall of the first aisle and in the upper one, besides the two previous ones the main nave and the second aisle, all of them ending in inclined planes, except the last one that being this nave perpendicular to the main one, it looks like a horizontal line. In the portico’s walls there is a large door in the shape of a round arch upon jambs and imposts and two big windows located upon its vertical; one of them is now blocked off; two other big windows are in the first aisles and a ceiling rose on the upper part of the wall. All the windows are decorated with lattice cutouts in stone, where the lower part of round arches upon small columns and capitals have been chiseled with great skill; and the upper one has been decorated with a ceiling rose or with new arches and other decorations that finish in a round arch.

the main nave and the two kinds of aisles. Its structure must have been very original for those times, since the two highest aisles, which only the western one has been preserved, would produce the false feeling that the church had two transverse naves as if it had two crossing naves. Its main façade is the most interesting one in all Spanish Pre-Romanesque art. Its composition consists of four different plans: in the portico’s lower part and in the wall of the first aisle and in the upper one, besides the two previous ones the main nave and the second aisle, all of them ending in inclined planes, except the last one that being this nave perpendicular to the main one, it looks like a horizontal line. In the portico’s walls there is a large door in the shape of a round arch upon jambs and imposts and two big windows located upon its vertical; one of them is now blocked off; two other big windows are in the first aisles and a ceiling rose on the upper part of the wall. All the windows are decorated with lattice cutouts in stone, where the lower part of round arches upon small columns and capitals have been chiseled with great skill; and the upper one has been decorated with a ceiling rose or with new arches and other decorations that finish in a round arch.

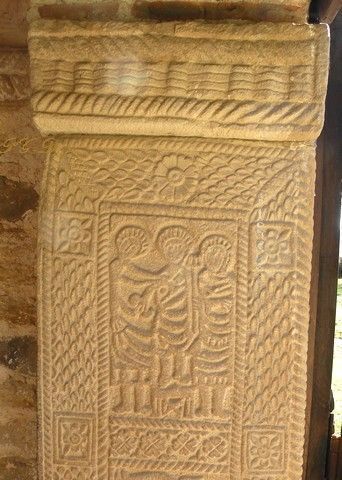

The sculptured decoration in San Miguel is as important as the one we have seen in Santa María del Naranco. The nave’s colums were plain upon square  bases decorated with human figures within arches and capitals in pyramidal shape that contained relieves of Byzantine type or Hispanic origin. The one of the high tribune had a strias decoration with square impost instead of capital and the tribune’s arches were surrounded by stone ovals roped in the edges and interior decoration of wheels and suns that recalls much of the Visigothic art. Even more important is the decoration of the entrance door’s jambs that contain scenes with human figures and seem to have been copied from a consular diptych of which a copy is kept in the

bases decorated with human figures within arches and capitals in pyramidal shape that contained relieves of Byzantine type or Hispanic origin. The one of the high tribune had a strias decoration with square impost instead of capital and the tribune’s arches were surrounded by stone ovals roped in the edges and interior decoration of wheels and suns that recalls much of the Visigothic art. Even more important is the decoration of the entrance door’s jambs that contain scenes with human figures and seem to have been copied from a consular diptych of which a copy is kept in the  Leningrad Museum. Based on everything mentioned above, we can figure out the level reached by the decorations from the now disappeared part of this church, especially with regard to the chevet of which a few remains have been found, like the altar that was later moved to Santa María and today we find it in Oviedo’s Museum. It has a great quality decoration that forms a frieze of ivy leaves. It is important to notice that here we see the human figure sculptured for the first time in Asturian art, which latest representations previously in Spain are found in monuments two centuries older, like San Pedro de la Nave or Quintanilla de las

Leningrad Museum. Based on everything mentioned above, we can figure out the level reached by the decorations from the now disappeared part of this church, especially with regard to the chevet of which a few remains have been found, like the altar that was later moved to Santa María and today we find it in Oviedo’s Museum. It has a great quality decoration that forms a frieze of ivy leaves. It is important to notice that here we see the human figure sculptured for the first time in Asturian art, which latest representations previously in Spain are found in monuments two centuries older, like San Pedro de la Nave or Quintanilla de las

Viñas. As we have indicated, it seems that the whole of the sculptured decoration was developed by a sole atelier, the same one that decorated Santa María, with the same technique that modifies the Visigothic two-plan-bevel one, making the volumes rounder to get a much softer and more realistic effect, and also with motifs of such different influences like the Byzantine, the Oriental, the Irish and the Hispanic.

Some rests of wall paintings have also been preserved in which we can find two very different types, one similar to the apses’ vaults of San Julián de los Prados and the other one with human figures that also appear in the Asturian Art for the first time and that have a close relationship with the “Mozarabic” called miniature.

Conclusions

In theses churches, as in Santa María del Naranco, we find ourselves with another great work of a genial architect that new how to merge the building and artistic techniques known up to then to create new buildings that went almost totally beyond what was usual at those times, with a complete previous planning and developed by a team that shows great maturity. In fact, the palatial ensemble of the Naranco Hill is one of the most important areas of all of the European Pre-Romanesque Art, to such an extent that the solutions implemented in these two monuments were so much ahead of its time that they could not even imitate them in the next period. Therefore, if we want to find again buildings with a similar structure we have to wait until the beginning of the Romanesque Art, over a hundred years later.

Other interesting information

Access: Go up from Oviedo’s downtown to the Naranco Hill through Padre Vinjoy, Hermanos Menéndez Pidal,Teniente Coronel Teijeiro and Ramiro I from the Plaza de la Paz ; then follow the signals. GPS Coordinates: 43º 22′ 49,20″N 5º 52′ 6,17″W.

Information telephone: Parish priest: 985 212 660 (D. José Luis Pascual Arias). Visits: 638 260 163

Visiting hours: The last visit starts always half an hour before closing. – Winter (October through April): Tuesdays to Saturdays: 10 to 13 and 15 to 17. Sundays and Mondays: 10:00 to 13:00. – Summer (May through September): Tuesdays to Saturdays: From 9:30 to 13:30 and 15:30 to 19:30. Sundays and Mondays: 9:30 to 13:30.

Bibliography

Arte Pre-románico Asturiano: Antonio Bonet Correa

SUMMA ARTIS: Tomo VIII

L’Art Préroman Hispanique: ZODIAQUE

Ars Hispanie: Tomo II

Arte Asturiano: José Manuel Pita Andrade

Guía del Arte Prerrománico Asturiano: Lorenzo Arias Páramo

Portals

Santa Maria del Naranco y San Miguel de Lillo (Página Oficial)

Reconstrucción de la iglesia de San Miguel de Liño: L. Arias Páramo

Iglesia de San Miguel de Lillo

La intervención en la arquitectura prerrománica asturiana: Jorge Hevia Blanco, Gema Elvira Adán Álvarez

Observaciones arqueológicas sobre producción arquitectónica y decorativa de las iglesias de S. Miguel de Lillo y Santianes de Pravia