SAN JULIÁN DE LOS PRADOS

Previous notes

- Fue declarada Monumento Nacional el 8 de junio de 1917 y Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la Unesco en 1998.

- Sufrió algunas modificaciones el siglo XVII, en las que se sustituyó el suelo original de “opus signinum“y se añadieron una galería y un antepórtico.

- Después de una primera restauración desde noviembre de 1912 hasta junio de 1917, llevada a cabo por Fortunato Selgas y Vicente Lampérez, en la que se descubrieron sus pinturas murales, estudiadas posteriormente por H. Schlunk y Magín Berenguer y restauradas en varias campañas desde entonces.

Historic environment

Mandada edificar por Alfonso II el Casto entre los años 812 y 842, dentro de un conjunto suburbano que incluía también un palacio, termas y otras dependencias, al parecer sobre una antigua villa romana, esta iglesia llamada popularmente “Santullano” y declarada Patrimonio de la Humanidad, es la de mayor tamaño que se conserva de todo el prerrománico español. Es también el único edificio que nos ha llegado en buen estado de conservación de los muchos que Alfonso II levantó en Oviedo, al trasladar a esta ciudad su capital.

Description

Built in small stone masonry and ashlars on the corners, it has a basilic plan of three naves separated by round arches in brick upon square pillars, with three apses, portico and a great transept nave, as wide and higher than the main nave, that has a compartment attached to each side. This nave is separated from the main one by a a wall opened by a triumphal arch and two windows: a structure that recalls us a characteristic already found in the Visigothic transition

Built in small stone masonry and ashlars on the corners, it has a basilic plan of three naves separated by round arches in brick upon square pillars, with three apses, portico and a great transept nave, as wide and higher than the main nave, that has a compartment attached to each side. This nave is separated from the main one by a a wall opened by a triumphal arch and two windows: a structure that recalls us a characteristic already found in the Visigothic transition

period: the quest of a way to utilize basilical plans adding some kind of transept that was required by the worship needs of those times. Its basilical plan, the entrance portico, the lack of a crossing tower, the quest of a way to separate the naves from the chevet through an atypical crossing and even the sensation of horizontality produced by the relationship of its width with respect to its height, makes us recall San Juan de Baños, despite the big differences, like the use of pillars in the separation arches and the shape of the crossing and the chevet; what makes us think in how we would have considered the relationship between the Asturian and the Visigothic arts had we known some of the monuments that existed in the big cities in that phase.

Anyhow, whatever their precedents are, it is obvious that we face one of the most important monuments of all Spanish Pre-Romanesque Art, not only for its size of 39m long by 29m wide, but also for the almost perfect conditions in which it has survived and the clarity through which we can study the main characteristics of all the Asturian art, excepting the three Ramirense buildings.

Its exterior image, despite the size of the crossing nave, is perfectly balanced in the composition of volumes presented by the ensemble of the naves, being the crossing nave quite higher than the main one and this one higher than the aisles, the three porticos and the tripartite chevet. The difference in height between the structural elements have let open windows of a much larger size than in the churches of the Visigothic period, decorated with ceramic lattice work, framed by four monoliths like in Santa Eulalia de Bóveda, and with a round discharging arch in brick, except in the ones on the walls of the main nave upon the aisles. A special mention deserves the chevet’s testero with buttresses that are also present on the lateral walls; a few windows in each apse and another one in the centre’s higher part, that has three round arches separated by columns upon decorated capitals and imposts, of great beauty overall.

Its exterior image, despite the size of the crossing nave, is perfectly balanced in the composition of volumes presented by the ensemble of the naves, being the crossing nave quite higher than the main one and this one higher than the aisles, the three porticos and the tripartite chevet. The difference in height between the structural elements have let open windows of a much larger size than in the churches of the Visigothic period, decorated with ceramic lattice work, framed by four monoliths like in Santa Eulalia de Bóveda, and with a round discharging arch in brick, except in the ones on the walls of the main nave upon the aisles. A special mention deserves the chevet’s testero with buttresses that are also present on the lateral walls; a few windows in each apse and another one in the centre’s higher part, that has three round arches separated by columns upon decorated capitals and imposts, of great beauty overall.

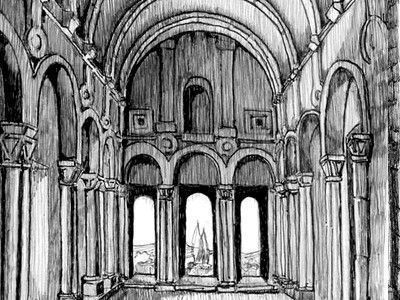

But the biggest impact we feel on entering. The first thing that stands out is the sensation of spaciousness produced by the width of the main nave, the lighting offered by the windows, quite unusual in Medieval monuments prior to the Gothic period, and the depth of the view of the wide crossing and the apses’ arches through the triumphal arch with which it communicates. Another element that calls our immediate attention is the collection of paintings that covered the whole interior of the temple, out of which a very important part is still preserved.

In fact we find ourselves before a series of elements that make Santullano a referent of almost all the Asturian architecture. The basilical area covered with a wooden skeleton consists of three naves being the main nave much higher and wider than the aisles; separated by three round arches in brick upon sqare pillars on bases and imposts. Upon each arch in the lateral walls of the main nave opens a window and in the separation wall with the transept, similar to San Giao de Nazaré, a triumphal round arch in brick, narrower than the nave at which sides two windows, also round arches – possibly because the architect did not want to risk making a larger opening, since another characteristic of this building is its sturdiness- that has let it persist in such excellent conditions after over twelve centuries.

In fact we find ourselves before a series of elements that make Santullano a referent of almost all the Asturian architecture. The basilical area covered with a wooden skeleton consists of three naves being the main nave much higher and wider than the aisles; separated by three round arches in brick upon sqare pillars on bases and imposts. Upon each arch in the lateral walls of the main nave opens a window and in the separation wall with the transept, similar to San Giao de Nazaré, a triumphal round arch in brick, narrower than the nave at which sides two windows, also round arches – possibly because the architect did not want to risk making a larger opening, since another characteristic of this building is its sturdiness- that has let it persist in such excellent conditions after over twelve centuries.

The sensation of amplitude increases when passing through the crossing’s arch of equal width than the main one but 2m higher, extending throughout the width of the three naves; a size unusual for a monument of this period, to which other characteristics are added, like its communicatiion with the basilical part by three arches, one for each nave, and for the two windows that flank the main one. The opposite wall has three arches that communicate with each of the apses and two windows above the lateral apses; and there is a door at each side that lead to the lateral compartments. Whilst there is a big window in the southern wall, above the existing compartment of the northern side there was a sort of a tribune, communicated with the interior through a linteled opening so that the king could follow the ceremonies from a privileged place. Maybe the need to include this royal tribune was the main reason to have built the crossing’s nave higher than the main one.

door at each side that lead to the lateral compartments. Whilst there is a big window in the southern wall, above the existing compartment of the northern side there was a sort of a tribune, communicated with the interior through a linteled opening so that the king could follow the ceremonies from a privileged place. Maybe the need to include this royal tribune was the main reason to have built the crossing’s nave higher than the main one.

Even of higher interest is the group of the chevet, the only vaulted area and also the only one with sculptoric decoration.  It is formed by three apses covered by barrel vaults with a somewhat unusual distribution, since the central one is narrower than the main nave, perhaps due to the artist’s interest of not risking, whilst the lateral are much wider than those naves, so the group of ther chevet gets a bit narrower than the rest of the church. At each side of the central apse that counts with two series of blank arches upon reutilized columns and capitals, there is a smal round arch that communicates with the lateral apse of this side. As we have mentioned, there is a window facing east in the three apses, what makes an excellent lighting of the ensemble. A special mention deserves the compartment abover the

It is formed by three apses covered by barrel vaults with a somewhat unusual distribution, since the central one is narrower than the main nave, perhaps due to the artist’s interest of not risking, whilst the lateral are much wider than those naves, so the group of ther chevet gets a bit narrower than the rest of the church. At each side of the central apse that counts with two series of blank arches upon reutilized columns and capitals, there is a smal round arch that communicates with the lateral apse of this side. As we have mentioned, there is a window facing east in the three apses, what makes an excellent lighting of the ensemble. A special mention deserves the compartment abover the

central apse, similar to the ones we find in some Visigothic churches, like San Pedro de la Nave, but with the peculiarity that we will find again in other Asturian buildings like San Pedro de Nora, that while the Visigothics had a c ommunication window to the interior, the Asturians are only accessible from the outsde. A lot of speculations have been made but it is still unknown what was the use of these compartments of such a difficult access in both cases.

ommunication window to the interior, the Asturians are only accessible from the outsde. A lot of speculations have been made but it is still unknown what was the use of these compartments of such a difficult access in both cases.

But despite its imposing presence from the architectural stand point, a church built in the new Asturian capital buy a king that had the aim of restauring the Visigothic kingdom, had also to impress with a court decoration. As we have seen, San Julián de los Prados was quite poor in sculptoric decoration but it was provided with a complete pictorial programme that has reached to these days in a state that allows us to know it with sufficient accuracy because the paintings were engraved with a burin before being coloured.

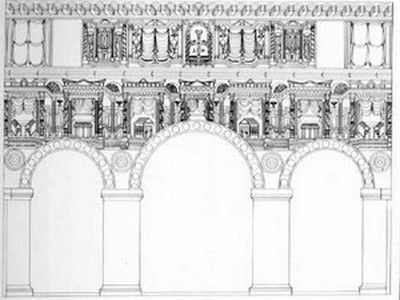

The paintings are placed in horizontal zones separated by horizontal lines imitating imposts. The basic range of colours is formed by the blue-grey, the ocher-yellow and the crimson-red, very similar to the Roman paintings. Several zones are clearly differentiated regarding its composition:

- The plinth: formed by a series of interwined squared with a row of other smaller squares and a frieze.

- The arcades’ zone: that only exists in the main nave and in the apses and it consists of big ovals around the arches with a decoration of concentric circles between them.

- The walls: is the most imoportant part and it is subdivided in two to three horizontal areas that contan architectural drawings of different characteristics and using different perspectives in each stripe. The view

from a window has been simulated in some of them through the inclusion of curtains that cover part of the building.

from a window has been simulated in some of them through the inclusion of curtains that cover part of the building. - The apses’ vaults: contain drawings formed by squares and hexagons and other interwined circles with floral motifs.

It is also interesting to point out the existence of triumphal crosses in several of these zones, an element so typical of the Asturian monarchy.

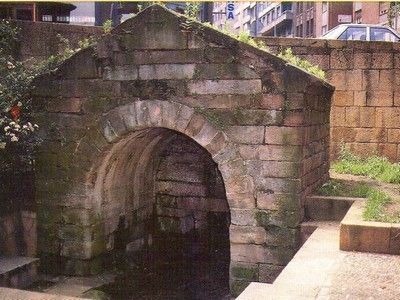

The interpretation of these paintings is a bit complicated. There is not any doubt about the relationship with the late Roman painting, but the perfection of such a complex programme as well as the situation of isolation of the Asturian kingdom in this period, lead us to think on the probable existence in the zone of former paintings that could have served as a model, either for the Visigothic period, of which we have information about excellently decorated temples though they have not reached to these days, or of Roman constructions that are still preserved in the area. For example, very near Oviedo we find the archaeological site of Veranes, today under study and consolidation. According to the investigators, it is a late Roman villa that was modified in the seventh century to convert one of its halls in a one nave church with a horseshoe arch shaped apse. A Highmedieval necropolis has been foud in its surroundings and it is known it was inhabited at least until the twelfth century. We can stress the similarity both in the utilized colours of San Julián de los Prados as well as in the drawings of the paintings of its apses with the mosaics found in Veranes. We do not know whether this villa had any wall paintings, although it seems quite logical that, had there been any, its is highly probable that they existed even in the times of the building of Santullano, in which case they could have been a reference. But that is not the important thing. What is interesting of what has been found in Veranes is that it shows the existence of a constructive and artistic continuity in Asturias between the Roman period and the ninth century, and therefore we must consider that Roman and Visigothic tradition as a very important reference at the moment of analysing, not only Santullano, but also all of the Asturian Pre-Romanesque Art..

Other interesting information

Access: Plaza de Santullano, Oviedo. Go up the General Elorza street from the Plaza de la Cruz Roja and follow the signals. GPS Coordinates: 43º 22′ 3,66″N 5º 50′ 13,97″W.

Information Telephone: Consejería de Cultura, Sol street Nº 8, 33009 Oviedo: 985 106 737 or 985 106 700

Visiting hours: Tuesdays through Fridays from 10:00 to 13:00 and from 16:00 to 18:00. Saturdays from 09:30 to 11:30 and from 15:30 to 17:30. Sundays from 10:00 to 13:00. Mondays from 10:00 to 13:30.

Bibliography

Arte Pre-románico Asturiano: Antonio Bonet Correa

SUMMA ARTIS: Tomo VIII

L’Art Preroman Hispanique: ZODIAQUE

Ars Hispanie: Tomo II

Portals

One thought on “SAN JULIÁN DE LOS PRADOS”

Leave a Reply

Wooden household furniture has something quite organic concerning it.

There is this sense of comfort, of attributes as well as of style that could

be be found in wood furnishings. Wood is born from the planet.

It feeds the fire, degenerates in to drafts and ashes away.

It is actually incredibly near to the human life on earth.

Might be actually that is why it sounds so much with our team.

May be actually that is why you still get that warm sensation when you contact a wealthy mahogany desk.

my webpage: learn more here