CARTAGHO SPARTARIA

Historic environment

The first time the city of Cartagena is named as Carthago Spartaria was in the Chronicon of the Hispano-Roman historian and bishop Hidacio (c.400-469) when describing its sacking by the Vandals in the year 425. Before it had been invaded by the Alans, who were expelled by the Visigothic king Walia, under the orders of Emperor Honorius, to restore Roman authority in the region. In 427, the Suevi from Ermengarius reclaimed the city, which led to the destruction of Carthago Spartaria and its fortifications by the Vandal king Gunderic, who later moved to North Africa with his people, leaving the city back in soft hands. In turn, these were defeated by the Hispano-Romans before the walls that had been built  again. Later, in 461, the so-called battle of Cartagena took place, between the Roman army of Mayoriano and the Vandala of Genserico, the Romans being defeated.

again. Later, in 461, the so-called battle of Cartagena took place, between the Roman army of Mayoriano and the Vandala of Genserico, the Romans being defeated.

The origin of the Byzantine Carthago Spartaria can be found in the year 552, when the Visigothic nobleman Atanagildo asked the Byzantines for military aid, who with Justinian in power had expanded through Italy and North Africa, to confront King Agila. . With the victory and subsequent coronation of Atanagildo, these Byzantines receive as a reward a series of territories in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, a coastal territory from Malacca (present-day Malaga) and Cartago Nova (Cartagena). The capital is established in Cartago Nova, which changes its name to Cartago Spartaria. During those 61 years, the city, which had always remained more Romanized than the rest of the Visigothic kingdom, recovered its Latin character, with the restoration of public buildings and palaces, the restoration of Roman customs and the religion continued to be Catholic, although with rites. Byzantines. The province was led by a “magister militum Spaniae”, a civil and military governor. One of these governors, Comenciolo, ordered the reconstruction of the city walls, as confirmed by a commemorative tablet, in what is considered the best Byzantine remains on the peninsula. Relations between Constantinople and Cartagena were very frequent throughout this stage, Cartagena being an enclave of vital importance for Byzantine interests.

But while this was happening in Carthago Spartaria, in the rest of the Visigothic kingdom internal struggles for religious reasons divided the rulers. Leovigildo wanted the Arian religion to be adopted throughout the territory, before which the south of the peninsula, much more Romanized and Catholic, proclaimed itself independent: Cartagena and the Mediterranean slope under the emperor of Byzantium, Betica, Seville and the Algarve , proclaiming Hermenegildo king. In this way, Cartagena became a refuge for those who were persecuted or wanted to go into exile. And therefore, it was the object of numerous attacks. Its governor, Cesáreo, asked the Emperor Heraclius for help, but did not receive it. Little by little all the Byzantine territory was lost, resisting only its  city thanks to the walls. The defeat of the governor Cesáreo and his flight left the city abandoned, and it finally surrendered to Suintila in 616, who proceeded to destroy fortifications, loot palaces and execute Byzantine troops.

city thanks to the walls. The defeat of the governor Cesáreo and his flight left the city abandoned, and it finally surrendered to Suintila in 616, who proceeded to destroy fortifications, loot palaces and execute Byzantine troops.

In the year 675 it continued to be the episcopal see as its bishop Munulo appears signing the acts of the Council of Toledo. And after the Muslim conquest of the peninsula, it would continue within the Visigothic kingdom of Teodomiro, although the name of Carthage does not appear in the capitulations to the Arabs in 825.

The entire current city of Cartagena is an archaeological site, which presents visitable spaces, in the historic hills and in the valleys and plains between them. From the roundabout in front of the Renfe station, you can go to the Punic wall and from here go into the interior of the city. From the town hall square, near the port, you can access the Byzantine quarter of the Roman Theater and late shopping area. Another sector that is recently acquiring great importance due to the samples it offers of its occupation in the Byzantine phase, is next to the already musealized area of El Molinete, in the same neighborhood.

The current city of Cartagena is a great example of well-signposted and easy-to-access guided tours and itineraries, an exceptional milestone in the good management of archaeological heritage.

Description

As we have already mentioned, one of the most important vestiges of the Byzantine period in the peninsula is the commemorative tablet of the construction of the walls by the governor Comenciolo under the power of the emperor Mauritius (582-602). It is preserved in the Municipal Archaeological Museum.

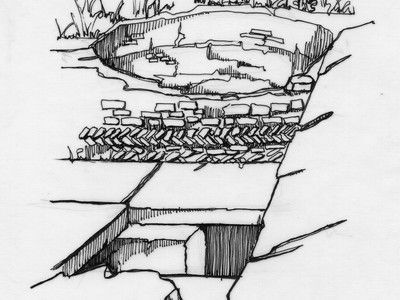

The remains of this wall have appeared in excavations on Calle de la Soledad and its surroundings. They are large blocks with the opus quadratum technique together with ceramic materials from the 6th century. It was the stretch of wall that surrounded the citadel, in turn located in a commercial district of the fifth century.

The discovery of the Roman theater in a nearby area served to conclude that the stretch of wall that appeared was a use of one of the porticoes that overlooked said theater.

The discovery of the Roman theater in a nearby area served to conclude that the stretch of wall that appeared was a use of one of the porticoes that overlooked said theater.

The wall can be visited in the lower part of the Municipal Exhibition Hall.

There are remains of two Byzantine neighborhoods, one on the slope of Cerro de la Concepción and the other in El Molinete, with modest buildings and lack of ornamentation. In the first of them, domestic materials such as combs or rings were found, as well as arrowheads or remains of armor plates of a lorica squamata of Eastern origin used by the Romans. It is not known if these buildings were warehouses, the residence of the garrison or for maintenance of the fortress. On the other hand, the structure of the El Molinete neighbourhood, with semi-detached houses, crooked alleys and irregular urban planning, indicates that it could be an artisan area, with at least one blacksmith shop and one pottery.

It is worth noting the excavation of a necropolis outside the walls, with grave goods consisting of African jugs, which would bear witness to the extensive commercial activity, and Byzantine bronze coins minted in the city itself, the nummi. The scarcity of female grave goods in said necropolis is striking.

And finally, the abundance of underwater remains in the Bay of Cartagena, especially in El Espalmador, may indicate that this land was the main anchorage for vessels used for trade between Spain and Africa, with the preservation of numerous wrecks such as the Punta of San Leandro or Bajo de Santa Ana.

The presence of the Iberian culture seems diffuse and late, the founding of a Punic city (Kart Hadasht) with a wall has left some remains, but it is the Roman colony of Nova Carthago, which It has allowed part of the forum, baths, theatre, amphitheatre, sanctuaries, roads, a large epigraphic collection, sculptures and archaeological pieces from all over the Mediterranean to be preserved. Its several historical hills stand out, highlighting since recent times the musealization of a part of the Molinete hill and the Roman public Roman structures that extend at its feet and give way to the entire Forum area. But it is the Byzantine phase, from the 6th and 7th centuries, that has bequeathed an exceptional Byzantine commercial district, to which can be added the new sector of the Molinete district.

The presence of the Iberian culture seems diffuse and late, the founding of a Punic city (Kart Hadasht) with a wall has left some remains, but it is the Roman colony of Nova Carthago, which It has allowed part of the forum, baths, theatre, amphitheatre, sanctuaries, roads, a large epigraphic collection, sculptures and archaeological pieces from all over the Mediterranean to be preserved. Its several historical hills stand out, highlighting since recent times the musealization of a part of the Molinete hill and the Roman public Roman structures that extend at its feet and give way to the entire Forum area. But it is the Byzantine phase, from the 6th and 7th centuries, that has bequeathed an exceptional Byzantine commercial district, to which can be added the new sector of the Molinete district.

It is a late city that serves as a great example of spolia, a huge reuse of a large amount of Roman material, which will be very useful in the late and Byzantine phase, with public spaces that change their function and with interesting late necropolises. It had an important Roman metropolitan episcopate that in the Gothic phase was supplanted by the new one of Toletum, when it became an authentic Urbs Regia in the 7th century, however, nothing of the Roman-Gothic and Byzantine Christian architecture has been preserved. On the other hand, the late necropolises of the city, from the 6th and 7th centuries, are well known, providing grave goods from the peninsula, but also from the Byzantine Mediterranean. It is also worth taking into account a good number of inscriptions on stone plates, written in both Greek and Latin, which are from this historical moment, highlighting the monumental one by Comenciolo. It is essential to visit the Municipal Archaeological Museum and the Theater Museum to see the materials recovered from this historical stage.

Elena Cardenal and Antonio Poveda for URBS REGIA

Other interesting information

The remains are located throughout the city and in the Archaeological Museum of Cartagena.

Museum hours: Tuesday to Friday: from 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. and from 5:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays: from 11:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m.

Half-hour or hour-long visits are recommended. The school visits are guided and for group visits you must make a reservation.

Free entrance

Bibliography

GARCIA del Toro, J.R., 1980: Cartago Spartaria : estudio histórico-arqueológico de la industria espartera en la Prehistoria y Edad Antigua en el Sureste, Academia Alfonso X El Sabio, Murcia

GÓMEZ CAPILLA, J.M., 2020: Acercamiento histórico-arqueológico a la Cartagena Bizantina: Carthago Spartaria, Cartagena

MAS García, J., 1986: Alta Edad Media. Siglos V al XIII. “Historia de Cartagena”. Tomo VI. Ediciones Mediterráneo.

RAMALLO Asensio, S.F., – RUIZ Valderas., 1996-1997: “E. Bizantinos en Cartagena. Una revisión a la luz de los nuevos hallazgos”, Annals de l’Institut d’Estudis Gironins, Nº 38, 1203-1221

VIZCAINO SÁNCHEZ, J., 2003: Carthago Spartaria en época bizantina. La documentación arqueológica, Universidad de Murcia, Departamento de Prehistoria, Arqueología, Historia Antigua, Historia Medieval y Ciencias y Técnicas Historiográficas.

Ruiz Valderas, E. (coord.), 2005: Bizancio en Carthago Spartaria. Aspectos de la vida cotidiana, Cartagena, 2005.

ID., 2009: La presencia bizantina en Hispania (siglos VI-VII). La documentación arqueológica, Anejos de Antigüedad y Cristianismo XXIV.

ID., 2019: “Carthago Spartaria, una plaza fuerte bizantina”, En tiempos de lo visigodos en el Territorio de Valencia, Diputación de Valencia, 155-163.

Portals