General Description

During the reign of Alphonse the Third, “The Great”, the boundaries of the kingdom of Asturias extend up to the Duero river, secured by a series of fortifications like Oporto, Toro, Zamora, Simancas, Dueñas or Burgos. This wide strip of land was repopulated mainly by people that came from the overcrowded north, looking for new spaces and by Mozarabics that were fleeing from the ever increasing problems for Christians in Al Andalus. Two human groups with many points in common that would create a new society and a renewed way of artistic expression where once again the horseshoe arch will be recovered.

“Mozarabic Art” is usually used to denominate the set of Christian artistic manifestations that took place in Al andalus and in the rest of the Iberian Peninsula between the beginnings of the 10th and the middle of the 11th centuries, that include horseshoe arches.

where they integrated easily, since both had kept the Visigothic cultural substratum and shared religion, culture, many of the customs and even a very concrete lithurgy clearly differentiated from those of the rest of the European environment.

where they integrated easily, since both had kept the Visigothic cultural substratum and shared religion, culture, many of the customs and even a very concrete lithurgy clearly differentiated from those of the rest of the European environment.

SPAIN IN THE TENTH CENTURY

This situation of tolerance prevailed for almost 150 years. A number of Christians, the so called muladíes, attracted by a superior culture and a much more pleasant style of life, became to arabize themselves and converted to Islamism, which also brought them fiscal privileges. Another important part of Christians, the so called Mozarabics, kept clung to their own customs, culture and religion within this permissive environment; although they were not allowed to build new churches, they were entitled to keep the existing ones int the seventh century.

This situation of tolerance prevailed for almost 150 years. A number of Christians, the so called muladíes, attracted by a superior culture and a much more pleasant style of life, became to arabize themselves and converted to Islamism, which also brought them fiscal privileges. Another important part of Christians, the so called Mozarabics, kept clung to their own customs, culture and religion within this permissive environment; although they were not allowed to build new churches, they were entitled to keep the existing ones int the seventh century.

-

By the year 850 an increasingly conversion, willingly or not, of a part of Christians to Islamism and their assimilation to that society, due to new pressures but also to the attractiveness that the Arabic culture had from an intelectual as well as from a material standpoint, started to poison the relationship between Arabs, Muladíes and Mozarabics which ended by generating a violent reaction in

the most orthodox Mozarabic faction. Led by Álvaro, a layman, probably of Jewish origin, and Eulogio, a clerk who became bishop of Toledo; both highly cultured; they left an important set of literary works of religious subject; generated a violent reaction among Christians who manifested their will to keep their identity in front of the increasing arabization that was taking place. An important group of Mozarabic led by San Eulogio, did not hesitate to become martyred if that meant the strengthening of the religious faith of their fellow Christians. Despite the extraordinary Council summoned in Córdoba by Abd-er-Rahman the second in 852, in an attempt to prevent the madness of public martyrdom of Christians, these did not change their attitude, that, besides generating around 50 martyrs in less thay ten years, enormously complicated the coexistence between Arabs and Christians. At the same time it awoke in Asturias the interest of what was going on there, in open expansion under the reign of Alfonso III el Magno, and in the Carolingian Empire, with big interests in the Marca Hispánica (Spanish March) that would later become Barcelona.

the most orthodox Mozarabic faction. Led by Álvaro, a layman, probably of Jewish origin, and Eulogio, a clerk who became bishop of Toledo; both highly cultured; they left an important set of literary works of religious subject; generated a violent reaction among Christians who manifested their will to keep their identity in front of the increasing arabization that was taking place. An important group of Mozarabic led by San Eulogio, did not hesitate to become martyred if that meant the strengthening of the religious faith of their fellow Christians. Despite the extraordinary Council summoned in Córdoba by Abd-er-Rahman the second in 852, in an attempt to prevent the madness of public martyrdom of Christians, these did not change their attitude, that, besides generating around 50 martyrs in less thay ten years, enormously complicated the coexistence between Arabs and Christians. At the same time it awoke in Asturias the interest of what was going on there, in open expansion under the reign of Alfonso III el Magno, and in the Carolingian Empire, with big interests in the Marca Hispánica (Spanish March) that would later become Barcelona.

-

In the second half of the ninth century, within a context of uprisings and tensions in the emirate, emerges Omar ben Hafsum, a muladí, son of Hafs -i.e., Alfonso- who heads an uprising against the emirate of Córdoba in the highlands of Antequera and Ronda and founds an independent kingdom with its capital Bobastro. After converting to Christianism, he manages to keep an independent kingdom for more than 50 years until after his death it was reconquered by Abd al-Rahman the third (912-961) in 928 (Among the ruins of Bobastro there is the only Mozarabic church known in Al-Andalus, on top a nearly inaccessible peak).

who in his forty-three years of reign he gave the definite impulse toward the Reconquest, expanding the conquest boarder till the Duero river, resettling with people coming from his reigns as well as with Mozarabics, founding villas and monasteries, protecting them with fortified cities like Oporto, Toro, Zamora Simancas or Dueñas, and creating the basis of the future Castille by building the fortress of Burgos. In the political area, he had united through matrimony with the royal family of Navarra and he gave a great impulse to recover all of Spain uniting the different Christian kingdoms under one “Magnus Imperator”, as his sons called him. Along this same line, he was a great supporter of culture and promoted the construction of civil works, especially in Oviedo and León, as well as churches and monasteries.

who in his forty-three years of reign he gave the definite impulse toward the Reconquest, expanding the conquest boarder till the Duero river, resettling with people coming from his reigns as well as with Mozarabics, founding villas and monasteries, protecting them with fortified cities like Oporto, Toro, Zamora Simancas or Dueñas, and creating the basis of the future Castille by building the fortress of Burgos. In the political area, he had united through matrimony with the royal family of Navarra and he gave a great impulse to recover all of Spain uniting the different Christian kingdoms under one “Magnus Imperator”, as his sons called him. Along this same line, he was a great supporter of culture and promoted the construction of civil works, especially in Oviedo and León, as well as churches and monasteries.

de Carolingian Empire and the Caliphate of Córdoba, until the half of the ninth century went through periods of Arab domination and others of relative independence, but it was basically dominated, as the French Navarra, by the Carolingian Empire. The independent domain of the Arista becomes consolidated as a consequence of a second victory over the Franks in 824 in Roncesvalles (do not mistake with the year 778 that gave origin to the legend of Roldán) when Íñigo Íñiguez, considered the first king of Navarra, consolidates the independent domain of the Arista.A very troubled period followed with fights generally associated with the Arab kingdom of Zaragoza against the Cordovans, the Franks and even aginst the Asturian kingdom.

de Carolingian Empire and the Caliphate of Córdoba, until the half of the ninth century went through periods of Arab domination and others of relative independence, but it was basically dominated, as the French Navarra, by the Carolingian Empire. The independent domain of the Arista becomes consolidated as a consequence of a second victory over the Franks in 824 in Roncesvalles (do not mistake with the year 778 that gave origin to the legend of Roldán) when Íñigo Íñiguez, considered the first king of Navarra, consolidates the independent domain of the Arista.A very troubled period followed with fights generally associated with the Arab kingdom of Zaragoza against the Cordovans, the Franks and even aginst the Asturian kingdom.

on being the set of counties that extended at both sides of the Pyrenees, depending from the Carolingian Empire with capital in Narbona: although as of 1000 the counts started to enjoy a relative independence. As a consequence, constructions pass from Visigothic to Mozarabic almost without a continuity solution and it is very difficult to precise in a large number of small rural churches that have survived, whether they are from the Visigothic period, old Visigothic constructions rebuilt later, or new constructions of what has been called Mozarabic Art.

on being the set of counties that extended at both sides of the Pyrenees, depending from the Carolingian Empire with capital in Narbona: although as of 1000 the counts started to enjoy a relative independence. As a consequence, constructions pass from Visigothic to Mozarabic almost without a continuity solution and it is very difficult to precise in a large number of small rural churches that have survived, whether they are from the Visigothic period, old Visigothic constructions rebuilt later, or new constructions of what has been called Mozarabic Art.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MOZARABIC PERIOD

-

Historical sources. Although with the necessary limitations of such a dark period, that have led to develop all kind of interpretations and theories, we count with an important corpus of knowledge about this period. This information comes from very different sources and environments like chronicles written by the Mozarabics from Córdoba, many chronicles from Asturias about the lst Visigothic years and the beginning of the Reconquest; chronicles from Navarra and Catalonia; multiple Muslim stories about these times; references to Spain in French chronicles and even other documentary sources like acts of foundation of monasteries or royal donations among others that provide wide information although not always coincident. We must also include in this section the first Castillian epic poems, like the one of Fernán González, written later but providing information about this period.

Historical sources. Although with the necessary limitations of such a dark period, that have led to develop all kind of interpretations and theories, we count with an important corpus of knowledge about this period. This information comes from very different sources and environments like chronicles written by the Mozarabics from Córdoba, many chronicles from Asturias about the lst Visigothic years and the beginning of the Reconquest; chronicles from Navarra and Catalonia; multiple Muslim stories about these times; references to Spain in French chronicles and even other documentary sources like acts of foundation of monasteries or royal donations among others that provide wide information although not always coincident. We must also include in this section the first Castillian epic poems, like the one of Fernán González, written later but providing information about this period.

-

Literature. It is a period of important development of religious literature as a continuation of the Isidoriano splendor of the previous phase where we can underline all the production of Álvaro and San Eulogio de Córdoba, the several Christian writers which the latter one refers to in his writings about his stay in Navarra; all of the production of the “scriptorium” from León and Castille and even the poems of the Spaniard Teodulfo in Carlomagno’s court. To that we have to add all the literature that is included in the Hispanic-Visigothic lithurgy which is especially rich in this period.

-

Music. It was also a period of musical creativity, at least in the lithurgical area. Thanks to cardinal Cisneros, antiphonaries containing lithurgical chants of the whole year and chants of the Visigothic period, as well as those developed in the Arabic zone, and the later musical flourishment in monasteries of León and Castille have been preserved to these days.

-

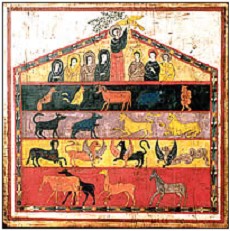

Miniature. A basic facet in Mozarabic art is the magnificent set of manuscripts that have been preserved from that period. The art of the miniature reached an extraordinary level in León and Castille along the tenth and eleven

centuries. Starting from the Isodorian tradition and the importance reached in all of Europe of the “Comments on the Apocalypse”, written by the Beato de Liébana at the end of the eight century, antiphonaries were created in the “scriptorium” of the monasteries like San Miguel de la Escalada, Albares, Albelda, San Millán de la Cogolla or Tábara. Among others, copies of the comments of Beato de Liébana, bibles and other illuminated manuscripts of an extraordinary quality and originality, highly superior to what was available in Europe till those times.Its influence was fundamental in miniature and Romanic painting through some manuscripts donated to monasteries of the Marca Hispánica and copied within them. Even the relationship with some artistic trends of the twentieth century is evident. As an example we can recall the parallel between some images of Picasso’s Guernica and the Bible of Isidoro de León from 960.

centuries. Starting from the Isodorian tradition and the importance reached in all of Europe of the “Comments on the Apocalypse”, written by the Beato de Liébana at the end of the eight century, antiphonaries were created in the “scriptorium” of the monasteries like San Miguel de la Escalada, Albares, Albelda, San Millán de la Cogolla or Tábara. Among others, copies of the comments of Beato de Liébana, bibles and other illuminated manuscripts of an extraordinary quality and originality, highly superior to what was available in Europe till those times.Its influence was fundamental in miniature and Romanic painting through some manuscripts donated to monasteries of the Marca Hispánica and copied within them. Even the relationship with some artistic trends of the twentieth century is evident. As an example we can recall the parallel between some images of Picasso’s Guernica and the Bible of Isidoro de León from 960.

-

Painting. It is the less known area and the one that requires more complicated analysis. At the beginning, according to the documentantion of those times, we know of the existence of an important pictorical tradition based in the caliphal art, and we have enough proof that in that period many churches were decorated with with frescoes like the ones found in the church of Wamba. But in some cases, like San Baudelia de Berlanga, the dating is not clear; in others it has not been studied enough, and besides, new rests have appeared now of paintings that had not been known before that are being now under scrutiny and restauration. Among the latter, the latest discoveries of frescos in churches like Santiago de Peñalba or San Miguel de Berlanga, still in phase of pre analysis.

-

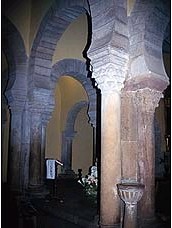

Sculpture. In this phase, sculpture is always plain, generally chiseled, following the technique of previous periods and the subjects are usually vegetal and geometric, with very few examples of figurative subjects. They are usually placed in capitals and in some cases of great beauty, like San Miguel de Escalada or San Cebrián de Mazote. A special mention deserves the decorations with geometric drawings of the modillions in stone or wood that support the eaves in almost all constructions.

-

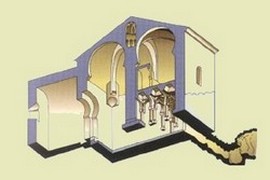

Architecture. AWhen it comes to analyse the most important characteristics of the so called “Mozarabic Art”, we find there are only three basic peculiarities. The one considered as the most important one is the uitilization in all cases of the horeseshoe arch; another one is that in almost all the churches the door is located at one side; and the third one -as we will explain later, and we think it to be even more important- is the absence of any other common characteristic.

-

In fact, in all the Christian constructions of that period – generally churches-, from the structure point of view we find

ourselves with any type of shapes , in the plans as well as in the elevations. There are basilic types of one, two and three naves, that in some cases are continuous and of the same height, but in others, they are generally divided in three flights, very much differentiated in the interior and in the exterior: cruciform or pseudo-cruciform churches or even, as is the case of San Baudelio de Berlanga, an actual cube with an apse and a double storey in the interior. There are churches with one, two and three apses and sometimes with opposite apses. As far as coverings are concerned, there are totally vaulted churches, with very sophisticated, imported techniques of the Arabic art, and others with plain wooden roofs; the same thing happens withe the material used; it is of all kinds, from the simplest masonry till constructions of perfectly carved ashlars. The form of decoration is also varied although in some cases common lines can be found, like the large decorated modillions in stone or wood, some series of capitals or the cases where frescoes have been found, with some similarities and details that we think they are enough so as to be able to define a style.

ourselves with any type of shapes , in the plans as well as in the elevations. There are basilic types of one, two and three naves, that in some cases are continuous and of the same height, but in others, they are generally divided in three flights, very much differentiated in the interior and in the exterior: cruciform or pseudo-cruciform churches or even, as is the case of San Baudelio de Berlanga, an actual cube with an apse and a double storey in the interior. There are churches with one, two and three apses and sometimes with opposite apses. As far as coverings are concerned, there are totally vaulted churches, with very sophisticated, imported techniques of the Arabic art, and others with plain wooden roofs; the same thing happens withe the material used; it is of all kinds, from the simplest masonry till constructions of perfectly carved ashlars. The form of decoration is also varied although in some cases common lines can be found, like the large decorated modillions in stone or wood, some series of capitals or the cases where frescoes have been found, with some similarities and details that we think they are enough so as to be able to define a style.

Hits: 4