SANTA EULALIA DE BÓVEDA

Previous notes

- Discovered a few years earlier and given to know in 1926. It was declared National Monument in 1931 and Heritage of Cultural Interest in 1996.

- Since its discovery it has gone through several interventions and studies, that in some cases have generated more damage than infomation and have not achieved so far to date its initial construction nor its consecutive modifications.

Historic environment

We find ourselves in front of one of the best singular buildings of all Spanish architecture.

From this monument, that had not been thoroughly studied until 1947, we know it was recorded on a document of the 8th century, where the upper church of Santa Eulalia is mentioned. This indicates it  was a double plan building and that its lower vault was damaged when the upper plan was tried to be fitted out for burials. It is now manifested as a series of unknown factors, extremely difficult to decipher due to the existing incompatibilities between some typical characteristics of the Roman architecture, as the painting in the interior decoration and the design of its structure, clearly classical; and others of basically barbarian and pagan sign, like the sculptured decoration of the external walls or the existence of a nave’s entrance door with the most ancient horseshoe arch in Spanish architecture as a structural element, as before then, it had only appeared in the decoration of some Roman steles.

was a double plan building and that its lower vault was damaged when the upper plan was tried to be fitted out for burials. It is now manifested as a series of unknown factors, extremely difficult to decipher due to the existing incompatibilities between some typical characteristics of the Roman architecture, as the painting in the interior decoration and the design of its structure, clearly classical; and others of basically barbarian and pagan sign, like the sculptured decoration of the external walls or the existence of a nave’s entrance door with the most ancient horseshoe arch in Spanish architecture as a structural element, as before then, it had only appeared in the decoration of some Roman steles.

This makes dating very difficult, since if it were Roman or Paleo-Christian, it should be located in the 4th century, whilst we consider the carved decoration on the outside and, above all, the existence of the horseshoe arch, it could be thought as a Swabian construction of the 6th century.

Description

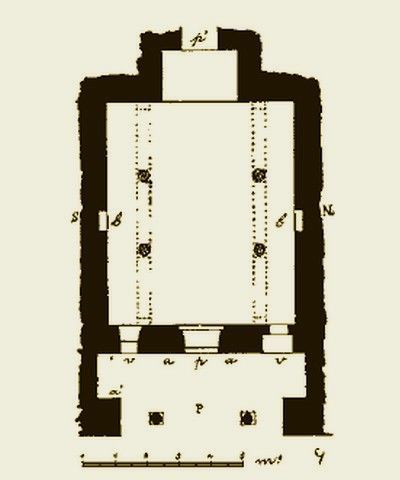

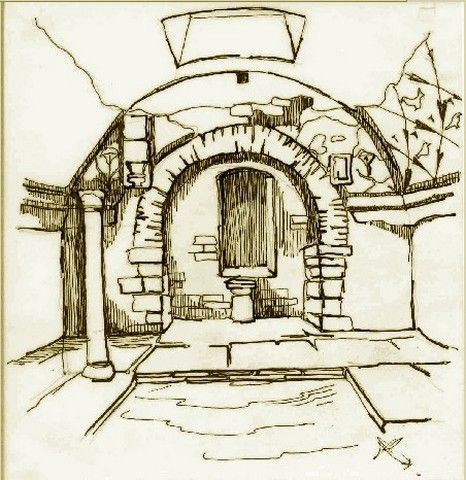

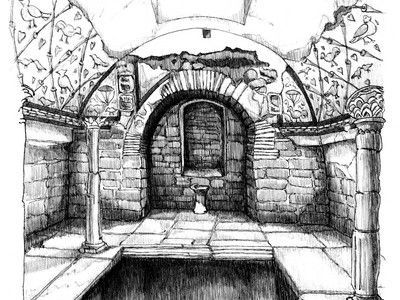

The original building consists of a sort of double vaulted crypt, with a structure similar to that of San Antolín in the Palencia Cathedral; squared shape, around 6 m by side, floored in alabaster with a pool in the middle that has at one end a quadrangular niche of around 3 m wide by 1 m deep, and the entrance at the opposite with a rectangular nartex and a portico before two columns that supported three arches, now disappeared, being the central one the widest. The building’s interior was later modified, reorganizing it longitudinally by adding two three arch rows, so each row was supported upon the walls and in two columns added for that purpose.

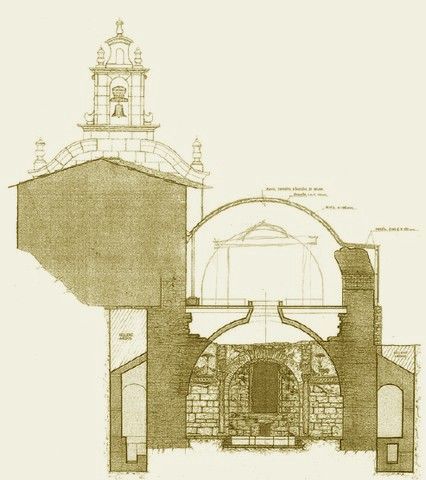

The original building consists of a sort of double vaulted crypt, with a structure similar to that of San Antolín in the Palencia Cathedral; squared shape, around 6 m by side, floored in alabaster with a pool in the middle that has at one end a quadrangular niche of around 3 m wide by 1 m deep, and the entrance at the opposite with a rectangular nartex and a portico before two columns that supported three arches, now disappeared, being the central one the widest. The building’s interior was later modified, reorganizing it longitudinally by adding two three arch rows, so each row was supported upon the walls and in two columns added for that purpose. mind that in the rear side the floor level was at the same height than the lower vault, since the building is buried on that side. We can also suppose that the upper nave was also covered by a barrel vault with a saddle roof. It is also possible that the referred door was a horseshoe one, as the three portico’s arches, like the one that is still preserved.

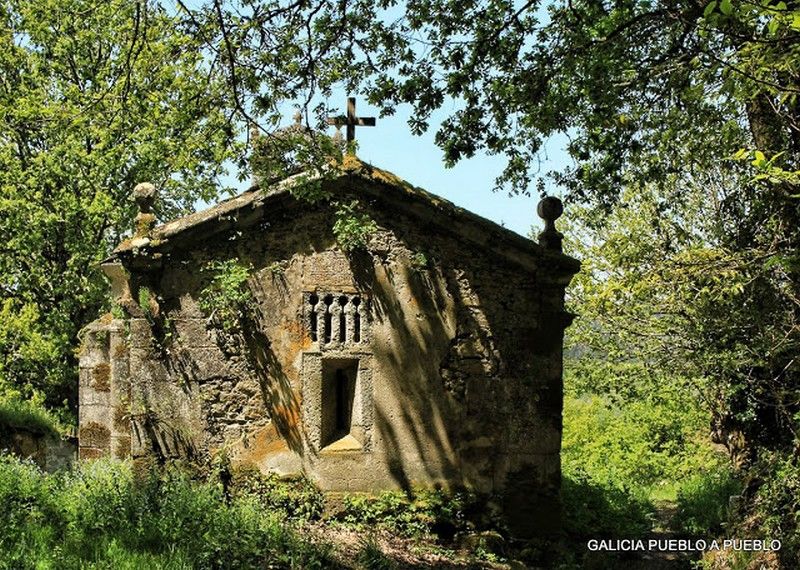

mind that in the rear side the floor level was at the same height than the lower vault, since the building is buried on that side. We can also suppose that the upper nave was also covered by a barrel vault with a saddle roof. It is also possible that the referred door was a horseshoe one, as the three portico’s arches, like the one that is still preserved. olonging a fourth of the radius, what would have been less surprising for a Visigothic church of the 7th century. In some of the stones of the façade a sculptured decoration may be noticed, clearly of the same period of the original construction, that consists of dancing figures that have no relation with the Roman sculpture.

olonging a fourth of the radius, what would have been less surprising for a Visigothic church of the 7th century. In some of the stones of the façade a sculptured decoration may be noticed, clearly of the same period of the original construction, that consists of dancing figures that have no relation with the Roman sculpture.It is also worth mentioning the later modification of the building, when the single nave was divided by adding two semi circular three-arch rows, of which the springline of the sidewalls have been preserved, that leaned upon four columns with capitals, two of them attached to the walls of the portico and the chevet. Each of the ensembles supported a separation wall that, besides reinforcing the vault, give it artificially the looks of a three nave basilical structure, possibly with the purpose of making it look more like a church than as the heathen temple it was originally conceived for; for that reason, the pool was topped with stones and was not discovered until 1947.

Still, traces have been preserved of a nave that originally existed upon the lower one we have described. This allows to include St. Eulalia de la Bóveda among the group of double vault monuments started in Spain with the Mausoleum of La Alberca and that we later find in the crypt of St. Antolín in the Cathedral of Palencia, The Holy Chamber of Oviedo and St. María del Naranco. There are doubts whether the remnants preserved in the upper nave correspond to the original building or they are a later high medieval restoration. In the sketch we include about its original structure, as a result of our visit to Bóveda in 1979, we have taken into consideration that on the western side, the level of the ground has the same height than the lower vault, since the building is buried on that side- Supposedly, the upper nave was also covered with a barrel vault with saddle roof.

Given its atypical characteristics, multiple theories have been generated regarding its origin, dating and succession of modifications it has gone through centuries. Despite the attention dedicated for over a century, at present it is a host of unfathomable queries due to the existing incompatibilities between some characteristics that are typical from the Romanesque art, such as the paintings that decorate the inside and the design of its initial structure, unquestionably classic, and others with a heavy barbarian and heathen design, as the decoration carved on the external walls or the existence of an entrance door to the one horseshoe arch nave, considered as the most ancient one in Spanish architecure as structural element, since previously, this kind of arches had only appeared in the decoration of some Roman steles.

Given its atypical characteristics, multiple theories have been generated regarding its origin, dating and succession of modifications it has gone through centuries. Despite the attention dedicated for over a century, at present it is a host of unfathomable queries due to the existing incompatibilities between some characteristics that are typical from the Romanesque art, such as the paintings that decorate the inside and the design of its initial structure, unquestionably classic, and others with a heavy barbarian and heathen design, as the decoration carved on the external walls or the existence of an entrance door to the one horseshoe arch nave, considered as the most ancient one in Spanish architecure as structural element, since previously, this kind of arches had only appeared in the decoration of some Roman steles.

If to all of that we add the new theories that tend to delay at least in two centuries the dating of churches that have been considered as Visigothic from the 7th centuries, and that up to now (2010) it has not been possible to establish an accurate scientific dating of the materials used in St. Eulalia de la Bóveda, it becomes very difficult to reach a conclusion regarding its origin and the different construction phases, although the following information may be considered as proven. facts, which reference is included in the existing bibliography at the end of this file:

- The whole perimeter strucrure of the lower storey, nave, vault, apse and nartex are coeval and belong to the original building.

- The pool, that was larger than the present one, as well as the complicated water supply system that entered through the niche on the bottom and allowed to keep the water level of the pool, also belongs to the first phase.

- The division into three naves was accomplished in the second phase. It was then, according to the studies achieved by the CSIC in 2009, that the door, initially linteled, was modified by adding a horseshoe arch, and paintings were created that spread out homogeneously throughout the original walls and the new row of arches. Also the pool was covered by then with marble slabs.

Conclusions

arch, but we know that these had appeared earlier as a decoration of some Roman steles in the north of Spain. Accordingly, the sculptured decoration could have Celtic influences on account of the style and clothing of the dancers. This theory is based on the existence of the pool and of a complicated system of water conduction, that entered through the bottom niche allowing to keep the level of water in the pool, what makes us think on a religious kind of rite related with water. The ensemble is a singular example of Hispanic-Roman syncretism.

arch, but we know that these had appeared earlier as a decoration of some Roman steles in the north of Spain. Accordingly, the sculptured decoration could have Celtic influences on account of the style and clothing of the dancers. This theory is based on the existence of the pool and of a complicated system of water conduction, that entered through the bottom niche allowing to keep the level of water in the pool, what makes us think on a religious kind of rite related with water. The ensemble is a singular example of Hispanic-Roman syncretism.

Other interesting information

Access: Sta. Eulalia de Bóveda (27233) LUGO, freeway A6 up to exit 523; take N-VI southbound, some 4 Km.

GPS Coordinates: 42º 58′ 48,67″N 7º 41′ 9,24″W.

Information Telephione: (034) 609 237 779

Visiting Hours: open all the year round. Ask for timetable.

Bibliography

L’Art Preroman Hispanique: ZODIAQUE

SUMMA ARTIS: Tomo VIII

Ars Hispanie: Tomo II

Portals

Santuario de Cibeles La Magna Mater (Santa Eulalia de Bóveda)

Santa Eulalia de Bóveda

Evolución constructiva de Santa Eulalia de Bóveda

Santa Eulalia de Bóveda: ochenta años de bibliografía

El descubrimento y las actuaciones arqueológicas en Santa Eulalia de Bóveda

Posibilidades de la aplicación de la Arqueología de la Arquitectura en Santa Eulalia de Bóveda