SAN GIAO DE NAZARÉ

Previous notes

- We know that, according to chronicles of that time, it was in good shape by 1597. It was rediscovered in 1961 and declared National Monument in 1986. Severely deteriorated, it had been used as a warehouse of a farm, after a reconstruction in the 18th century.

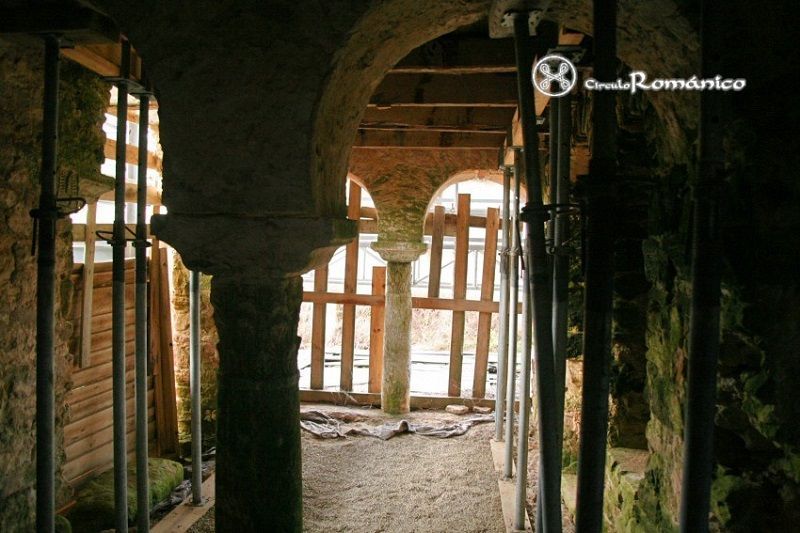

- Its study and restoration started a few years later but the work was interrupted due to disagreements between the owners and the Administration.

- It went through an archaeological analysis of its architecture by L. Caballero and his team in 2002.

Description

It is the high medieval monument with the most conflicting dating. Initially it was thought to be a Visigothic church upon a previous Early Christian settlement, but there are too many details in its structure that raise doubts with regard to the origin of the different elements that have reached until now.

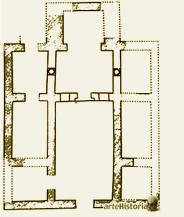

Inlaid in a rectangle, of which only the chevet comes out, it consisted of a nave of 6.60×3.90m between two walls 6.75m high with two parallel annexes compartmentalized similar to Quintanilla de las Viñas, a transverse nave forming a sort of a crossing and a square apse in the chevet with two apsidioles at the sides, upon the nave of the crossing, of semi circular plan, obviously built later. At the end of the naves there was a nartex with one only main door, supporting the gallery. It is practically certain that the church had a wooden cover except the chevet that must have been barrel vaulted following the shape of the entance arch.

of a nave of 6.60×3.90m between two walls 6.75m high with two parallel annexes compartmentalized similar to Quintanilla de las Viñas, a transverse nave forming a sort of a crossing and a square apse in the chevet with two apsidioles at the sides, upon the nave of the crossing, of semi circular plan, obviously built later. At the end of the naves there was a nartex with one only main door, supporting the gallery. It is practically certain that the church had a wooden cover except the chevet that must have been barrel vaulted following the shape of the entance arch.

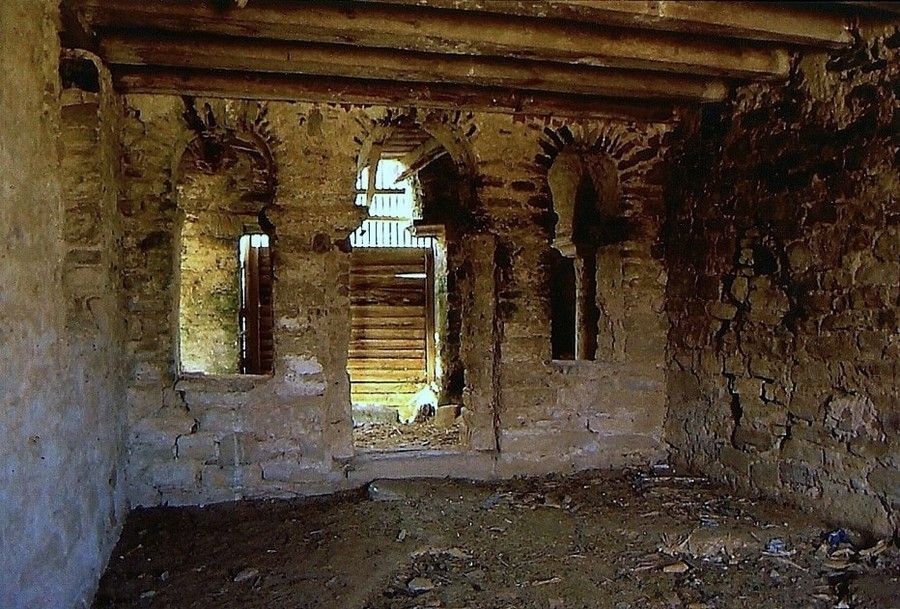

The structure of the central square is a very interesting one, not only for being atypical, but also for its very original design and the pleasant visual impact it provokes, with an opening to the chevet, two to each side of the crossing and three to the central nave. Its communication with the apse was by means of a triumphal  horse shoe arch, upon two magnificent imposts that had a part wider, inlaid in the wall with vegetal decoration, and another one narrower where the column with capital leaned, now disappeared. At each side of the crossing there were two stilted arches that set in the walls upon decorated imposts, that joined upon a central column, whereas between the central and the crossing nave there is a wall where three spans open producing a separation between both, similar to the one we frequently find in Asturian churches, like San Julián de Los Prados; a rounded stilted arch upon lateral imposts that are in very bad shape, and two symetrical windows at 80cm from the floor, also ending in rounded arches. Each one of the lateral naves communicated with the transverse one by means of a narrow door and with symetrical windows, with the nave.

horse shoe arch, upon two magnificent imposts that had a part wider, inlaid in the wall with vegetal decoration, and another one narrower where the column with capital leaned, now disappeared. At each side of the crossing there were two stilted arches that set in the walls upon decorated imposts, that joined upon a central column, whereas between the central and the crossing nave there is a wall where three spans open producing a separation between both, similar to the one we frequently find in Asturian churches, like San Julián de Los Prados; a rounded stilted arch upon lateral imposts that are in very bad shape, and two symetrical windows at 80cm from the floor, also ending in rounded arches. Each one of the lateral naves communicated with the transverse one by means of a narrow door and with symetrical windows, with the nave.

The shape of the access doors is very surprising, one at the end of the central nave and the other one at the left side, rectangular, with lintel and semicircular relieving arch, in the most pure Asturian style.

Conclusions

The analysis of San Giao is a very controversial one. The first sensation it produces, both internally and externally, is that of an Asturian church, since the separation wall between the central and the crossing naves is one of the most meaningful characteristics, and with a high visual impact, of the Asturian art in times of Alphonse the Second. Adding to that the similarity of the entrance doors, with lintel and relieving arch, the existence of two round stilted arches and the nartex’ with a raised gallery. However, the distribution of the chevet, as well as the entrance arch and a great part of the decoration found, are clearly Visigothic of the 7th century.

the existence of two round stilted arches and the nartex’ with a raised gallery. However, the distribution of the chevet, as well as the entrance arch and a great part of the decoration found, are clearly Visigothic of the 7th century.

Therefore, the first possibility to bear in mind is that it is a Visigothic church of the 7th century, that was brought down by the Arabs, except the chevet and rests of decoration, and rebuilt in Asturian style two centuries later. The problem is that it does not look at all probable that the Christians could have built a monastery in Nazaré around the year 900, since according to what is known so far, although they dominated Coimbra from the year 880, they did not conquer Santarém until 1064 and Lisbon until 1147. And all seems to indicate that Nazaré, 111Km south of Coimbra and so close to Santarém, would not be liberated until after 1050, a period when a reconstruction in Asturian syle would be unthinkable, both, for historical reasons and for no  coincidences with this style that would have been built by Mozarabics. And San Giao does not offer any characteristic that recalls the first Romanesque period in which it was being built already in times of Alphonse the Sixth. Besides, the separation between the nave and the chevet does not fit with the Christian rites of that period.

coincidences with this style that would have been built by Mozarabics. And San Giao does not offer any characteristic that recalls the first Romanesque period in which it was being built already in times of Alphonse the Sixth. Besides, the separation between the nave and the chevet does not fit with the Christian rites of that period.

It is also very difficult to put forward the possibility that all the building that has reached until now was 7th century Visigothic, because in that case we should accept the idea that in Visigothic architecture of that period, besides the cruciform churches that we know, the direct precedent of the churches of the first Asturian art was being cretaed, with a separation wall between the nave and the chevet, gallery and, even more difficult to believe, the round arch was being utilized again.

Nevertheless, before giving up this possibility completely, it is important to consider that, as no rests of any Visigothic construction in the great cities have reached until know, except some loose rests of its decoration, the knowledge we have of that architecture in the 7th century is limited to the magnificent, though not that much meaningful, monastic churches, built in rural areas and with a very different purpose to the basilics, in important cities. There are meaningful details, such as the size of the basilic of Cabeza de Griego, located in an urban centre, not very big, but with episcopal see, much superior to that of all rural churches, or the structure of Quintanilla, clearly Visigothic but, as we have seen, with many precedents of the first Asturian art.

Therefore, in order to reach a conclusion about the origin of San Giao, it is necessary to wait to know the conclusions of the study and of the restoration that are being accomplished now that, besides, could provide new information about the lesser known areas of High Medieval art in our peninsula.

REMARQUE : Grâce à notre accord avec URBS REGIA pour partager des informations sur les monuments entre nos pages, aux photos que nous incluons dans le texte, prises par nous vers 1980, qui montrent la situation de l’église dans ces années, nous avons pu inclure d’autres photos de sa restauration en 2005.

Other interesting information

Access: Leave Lisbon towards north by A8. Nazaré is 118Km far. The church is in the Quinta de San Giao, 5Km southwest of Nazaré, very near the sea.

e-mail address: Cámara Municipal – camaranazaregap@mail.telepac.pt

Visiting hours: Find out first as the monument is now being restored.

Bibliography

L’Art Preroman Hispanique: ZODIAQUE

Imagen del Arte Hispanovisigodo: Pedro de Palol

Historia de España de Menéndez Pidal: Tomo VI

Historia de España de Menéndez Pidal: Tomo VII(Sánchez Albornoz)

Portals