CÓDICE EMILIANENSE

Notas Previas

- Reference: Biblioteca del Monasterio del Escorial, (sig. D.I.1).

- Other names: Códice de los Concilios.

- 476 folios of parchment written in Visigoth letters on two columns.

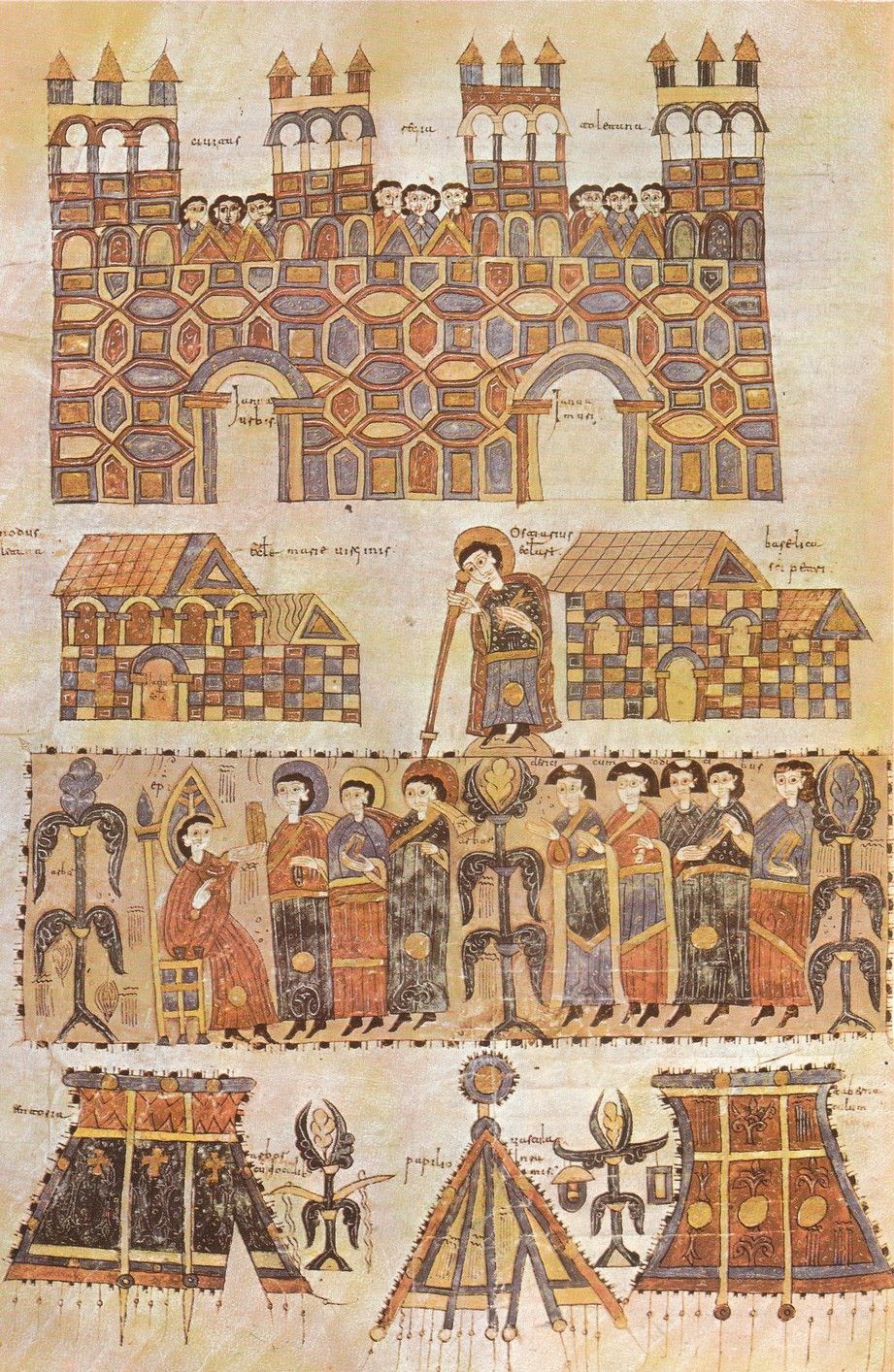

- More than 80 miniatures.

Entorno histórico

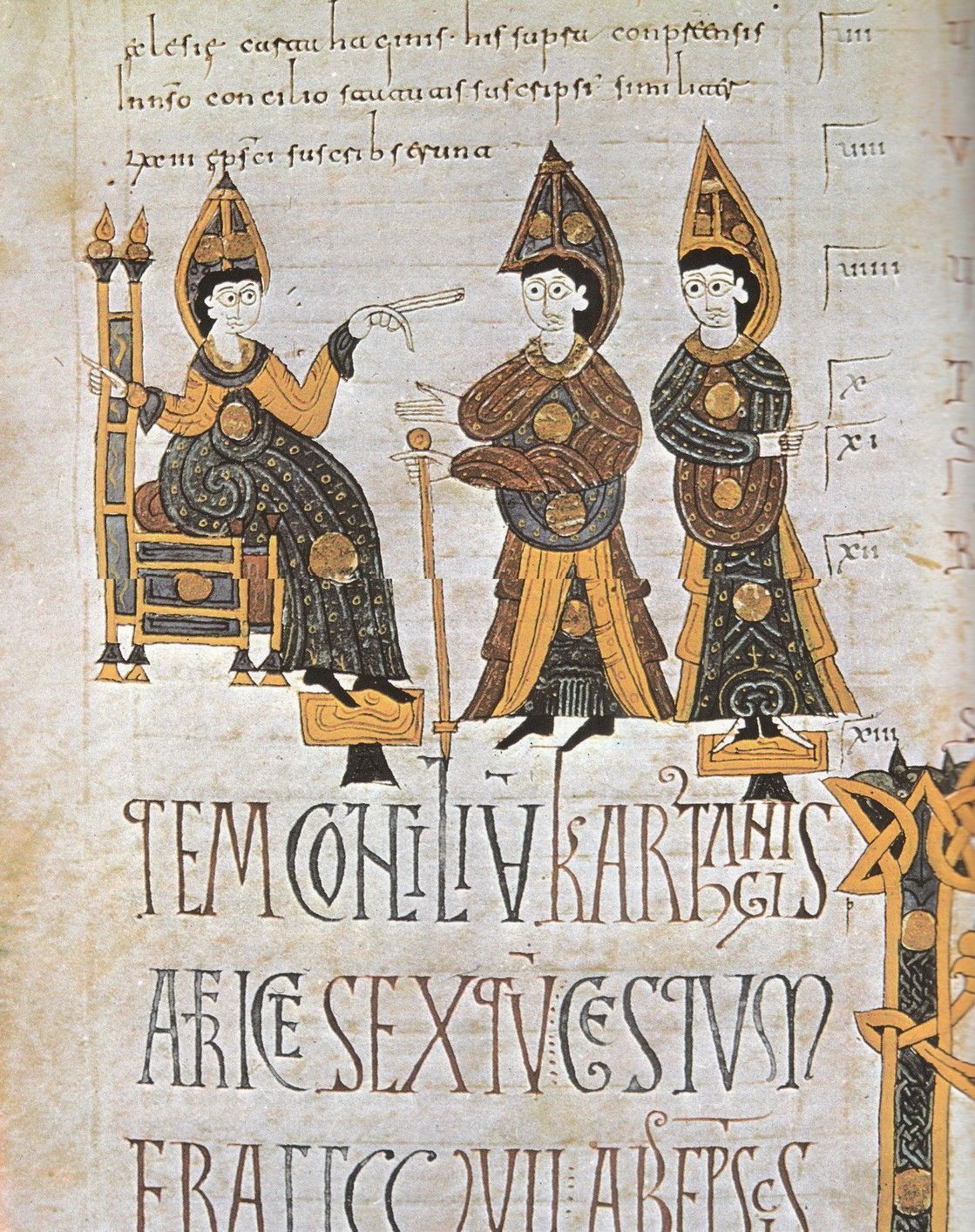

and it wasn’t over until 992. The work was directed by Bishop Sisebuto and developed by the copyist Belasco and the notary Sisebuto, according to the portraits of these three characters in one of the last folios of the manuscript.

and it wasn’t over until 992. The work was directed by Bishop Sisebuto and developed by the copyist Belasco and the notary Sisebuto, according to the portraits of these three characters in one of the last folios of the manuscript.

The mere fact that the Albeldense Codex was loaned for its copy to San Millán de la Cogolla so immediately, and remained there for so long, demonstrates the magnificent relations between the two monasteries and the interest that existed in immediately spreading the new books that were being created in the Spanish Christian scriptorium.

This codex has been in the Library of the Monastery of El Escorial since the 16th century. It was Ambrose of Morales who, within the commission he received from Philip II to search for ancient manuscripts throughout Spain to increase the funds of this library, obtained it from Pedro Ponce de León, bishop of Plasencia, who after his death in 1573 donated to El Escorial the rest of his library.

Descripción

As for its content includes, like the original Albeldense, the complete collection of the Spanish councils and the canons of all the general councils, the selection of canons and the decrees of the pontiffs up to Saint Gregory the Great, the Liber Iudiciorum and other texts of history or liturgy, such as the Albeldense Chronicle, the Prophetic Chronicle or the Life of Muhammad. Only very small changes in its content are observed, as the  initial poems, there is some modification in the order of presentation of the Canonical Collection and a pamphlet of Saint Isidore on ecclesiastical ministries and a list of Hispanic bishops and episcopal sees is added.

initial poems, there is some modification in the order of presentation of the Canonical Collection and a pamphlet of Saint Isidore on ecclesiastical ministries and a list of Hispanic bishops and episcopal sees is added.

However, in terms of his images, although he includes a number of miniatures and a layout very similar to those of the Albeldense Codex, the style is only maintained in the first folios. In the rest, although it preserves the themes and the way of presenting them, we find a great change in the treatment of the images, which begin to adjust to the style that can be defined as typical of the scriptorium of San Millán de la Cogolla, sinuous line parallel to the lower edge of the nose and bilobed ears that stand out on the hair. Clothes and their treatment also change, including a short apron or skirt in many of the characters and the vertical folds based on parallel lines are replaced by mantles that extend from the waist to the feet and in some of them have stepped sides; all this with an even richer decoration than in the albeldense. The color is also common in the production of San Millán de la Cogolla.

We also find details of style that are typical of Belasco and are not repeated in other manuscripts of the same origin, such as his tendency to use gildings with great profusion, not only in worship utensils and capital letters, but also in the decoration of clothes and animals. The hands are still large and in postures that give a sense of movement, but in this case the enormous size of the arms stands out, very disproportionate to the rest of the body.

This manuscript shows again the eclectic spirit of the Spanish early medieval culture and the great personality of the artists who developed at that time, because despite being a work focused exclusively on obtaining the first copy of a work of great transcendence, which was also developed in the Spanish scriptorium that had the most defined style, and although it also seems evident that its creator wanted to respect both aspects, in the Codex Emilianense we confirm again that the main sign of identity of each of the most interesting manuscripts of that time that have been preserved is the imprint of its author, but always within a spirit and framework of common artistic influences.

This codex also includes, copied from the Albeldense, the record of the nine Hindu-Arabic figures, making it the second known manuscript in which they appear written in the same format as is used today.

Bibliografía

Historia de España de Menéndez Pidal: Tomos VI y VII*

SUMMA ARTIS: Tomos VIII y XXII

L’Art Préroman Hispanique: ZODIAQUE

Arte y Arquitectura española 500/1250: Joaquín Yarza

Portales

Iconografía del siglo X en el reino de Pamplona-Nájera

El

escritorio de San Millán de la Cogolla

¿Hubo escritorio en La Cogolla durante el siglo VII?