SAN PEDRO DE LA MATA

Previous notes

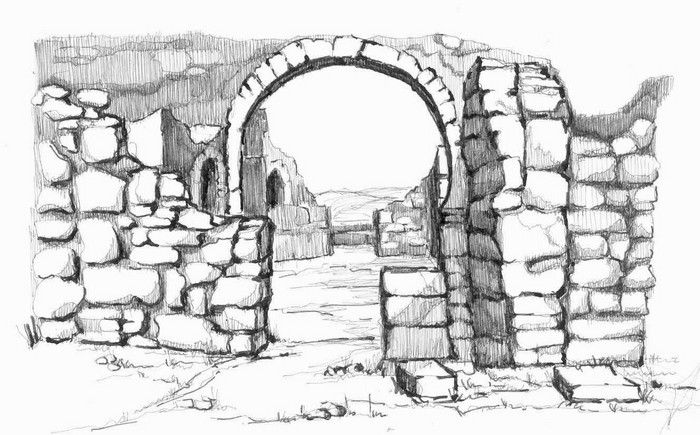

- Sólo se conservan restos de algunos de sus muros y no se conocen noticias de este edificio antes de su completa ruina.

- Concebida inicialmente como una iglesia cruciforme de planta semejante a Santa Comba de Bande y Santa María de Melque, su estructura fue muy modificada posiblemente por la inestabilidad que ya se debió detectar durante su construcción.

Historic environment

For its structural characteristics San Pedro de la Mata belongs to the cruciform Visigothic churches of the 7th century, together with Santa Comba de Bande and Santa María de Melque; however, this church links also with the best Toledan court art, according to the remains of decoration that have appeared and, as we shall see, for a modification in its structure with respect to the two former ones, it may be considered as a precedent of San Pedro de la Nave and Quintanilla de las Viñas. According to the most ancient reference that we know about it, a description of the 17th century, it was built in the times of king Wamba (672-681), which can be easily accepted given the high building spirit he had and also considering that the dating perfectly fits with the chronology we know of cruciform churches.

Description

Unfortunately, only remains of some walls in very bad shape have been left;  a part of those walls belong to later constructions that have disregarded the construction system and its original structure.

a part of those walls belong to later constructions that have disregarded the construction system and its original structure.

Following the 4/3 scale design of Santa Comba de Bande consisted initially of two naves that crossed at the crossing, forming a lantern upon horse shoe arches, of which only the southern side one is left, that, different to Bande, instead of leaning directly on shelves in the wall, they stem out over pillars attached to it and decorated marble imposts.

If the portico was also simetric to the apse, we find ourselves in front of a clear precedent of the type of church that will so magnificently develop in San Pedro de la Nave that, similar to this one, also has doors at the end of the crossing nave.

As we have mentioned in our notes on Bande, the lateral chambers were added later, what can be easily seen in the plans of separation that exist in the remains of the chevet, between the wall that corresponds to the apse and those of the lateral chambers.

In this church there are two special characteristics compared to the rest of the group, that may be in part responsible for the poor state of conservation despite steming out from a design that has resulted so robust: one is that it was built upon a huge stone slab, practically without any foundations. The other one is that its walls, made with ashlars, like all monuments of the 7th century, although its building technique is somewhat coarser, are considerably thinner, just 68cm, excepting those that form the apse, which are 1m thick.

built upon a huge stone slab, practically without any foundations. The other one is that its walls, made with ashlars, like all monuments of the 7th century, although its building technique is somewhat coarser, are considerably thinner, just 68cm, excepting those that form the apse, which are 1m thick.

The apse is separated from the main nave by a horse shoe arch with irregular voussoirs, some of them without extrados, extended in almost 2/5 of the radius below its centre, which now does not have the springings, formed by the decorated imposts, now disappeared, and most likely by capitals and columns like in Bande, although given the low thickness of the arch wall, there must have been here only one at each side. All of this suggests it was  covered by a barrel vault and, most likely, there was a chamber between it and the roof, accesible only through an interior window, as the one in Santa Comba de Bande.

covered by a barrel vault and, most likely, there was a chamber between it and the roof, accesible only through an interior window, as the one in Santa Comba de Bande.

We cannot know for certain how the naves and the lantern of the crossing were covered, but there are reasons to think that they were different to the rest and, although the limited thickness of the walls could make us think it would have been difficult to cover them with vaults, the  fact that they collapsed not much after they were built, supports this theory.

fact that they collapsed not much after they were built, supports this theory.

The remains left, with two lateral chambers attached along the apse’s chevet and the eastern nave and the other one attached to the south of the western nave, longer than the former one so that its wall is reinforced up to twice its original thickness, as well as the fact that the rest of the nave has disappeared, makes us think that the church must have shown quite early resistance problems since, the traces preserved at the northern side of that western nave show that, had it been another lateral chamber attached to it, of which nothing is left, this part was not reinforced as it was done with the one in the southern side. So we think that the reinforcement of the southern side was necessary or that the whole of the northern side did not exist already when the church was modified, which is very likely given the feeling of irregularity that this remains now produce.

With regard to the decoration, of which almost nothing is left in the ruins, it was based on friezes distributed throughout the building and formed by vegetal stems with palmettes and bunches, flowers, etc. Also remains of decorated stones have appeared reutilized in constructions of the near villages of Arisgostas and Casalgordo, with volutes and geometrical drawings in the most pure style of Toledo and Mérida.

Conclusions

in the building of the three churches that form tha basic nucleus of the group of cruciform churches. There is not any historical reference from Melque and its dating is very questionable, mainly for its lack of decoration, to the event that some considered it to be Mozarabic, but we have much more information of the two others. We know for certain that both had been built between 670 and 680 and the only doubt is which one was first. On the one side, the fact that San Pedro de la Mata was so close to Toledo makes us think that it was built first since it is quite normal that the innovations radiate from the capital to the provinces but, in spite of that, if we take into consideration the vicinity of Bande with Braga to which diocese it belonged, and its more similarity with the structure of the Mausoleum of San Fructuoso, we stand for the theory that considers Bande being earlier.

in the building of the three churches that form tha basic nucleus of the group of cruciform churches. There is not any historical reference from Melque and its dating is very questionable, mainly for its lack of decoration, to the event that some considered it to be Mozarabic, but we have much more information of the two others. We know for certain that both had been built between 670 and 680 and the only doubt is which one was first. On the one side, the fact that San Pedro de la Mata was so close to Toledo makes us think that it was built first since it is quite normal that the innovations radiate from the capital to the provinces but, in spite of that, if we take into consideration the vicinity of Bande with Braga to which diocese it belonged, and its more similarity with the structure of the Mausoleum of San Fructuoso, we stand for the theory that considers Bande being earlier. Other interesting information

Access: Leave Toledo toward south. After 25.7Km take TO-7001-V for 5.1Km until Casalgordo and the stream of Valhermoso.

GPS Coordinates: 39º 36′ 49,11″N 3º 59′ 13,77″W.

Visiting hours: The ruins are not enclosed and may be visisted any moment.

Bibliography

Historia de España de Menéndez Pidal: Tomo III

SUMMA ARTIS: Tomo VIII

L’Art Preroman Hispanique: ZODIAQUE

Ars Hispanie: Tomo II

Imagen del Arte Hispanovisigodo: Pedro de Palol

Portals

San Pedro de la Mata

Rutas del Arte Visigodo: Visigodo en Toledo

Iglesia de San Pedro de la Mata (Sonseca)